- Volume 60 , Number 2

- Page: 161–72

Relapses in leprosy patients after release from dapsone monotherapy; experience in the leprosy control program of the all Africa Leprosy and Rehabilitation Training Center (ALERT) in Ethiopia

ABSTRACT

Before implementation of multidrug therapy (MDT), leprosy patients who were clinically inactive, skin-smear negative and had been treated with dapsone monotherapy for at least 5 years (paucibacillary patients) or for at least 10 years (multibacillary patients) were released from treatment.An analysis was made of self-reporting relapses in 1081 paucibacillary (PB) patients and 1123 multibacillary (MB) patients who had been released in Addis Ababa and two rural districts of the leprosy control program of the All Africa Leprosy and Rehabilitation Training Center (ALERT). During an average period of 6.6 years after stopping dapsone, 44 relapses were diagnosed among the PB patients and 148 relapses among the MB patients. The overall relapse rate was 4.1 % or 7.2 per 1000 patient-years after release from treatment for PB patients and 13.2% and 24.8, respectively, for MB patients. The annual relapse rate in PB patients did not differ significantly from year to year. However the relapse rate for MB patients was significantly lower during the fifth to seventh years after stopping treatment compared with the first 4 years. Based on clinical findings there was a strong suspicion of relapse with dapsone-resistant bacilli in 40.4% of MB relapses. It is concluded that the relapse rate for PB patients is acceptable. However, the relapse rate for MB patients is considered too high. It is strongly recommended to administer to all MB patients, including those who have been on long-term treatment with dapsone and have become clinically and bacteriologically inactive, a 2-year course of MDT.

RÉSUMÉ

Les malades de la lèpre qui étaient cliniquement inactifs, présentaient des frottis cutanés négatifs et avaient été traités par une monothérapie à la dapsone pendant au moins 5 ans (paucibacillaires) ou au moins 10 ans (multibacillaires) ont été libérés du traitement avant l'application de la polychimiothérapie (PCT).On a analysé les rechutes notifiées spontanément chez 1081 patients paucibacillaires (PB) et 1123 multibacillaires (MB) qui avaient été libérés du traitement à Addis Abeba et deux districts ruraux du programme de lutte contre la lèpre du "All África Leprosy and Rehabilitation Training Center" (ALERT). Durant une période moyenne de 6.6. ans après l'arrêt de la dapsone, 44 rechutes ont été diagnostiquées parmi les patients PB et 148 rechutes parmi les MB. Le taux global de rechute était de 4.1% ou 7.2 pour 1000 personneannées après l'arrêt du traitement pour les patients PB et 13.2% et 24.8, respectivement pour ls patients MB. Le taux annuel de rechute des patients PB ne variaitpas significativement d'année en année. Cependant, le taux de rechute des patients MB était significativement plus faible de la 5è à la 7è année après l'arrêt du traitement que durant les 4 premières années. Des observations cliniques ont fait suspecter fortement une rechute avec des bacilles résistant à la dapsone chez 40.4% des rechutes MB. On en conclut que le taux de rechute des patients PB est acceptable. Cependant, le taux de rechute des patients MB est considéré comme trop élevé. Il est fortement recommandé d'administrer un traitement PCT de 2 ans à tous les patients MB, y compris ceux qui ont eu un traitement de longue durée à la dapsone et sont devenus cliniquement et bactériologiquement inactifs.

RESUMEN

Antes de la implementación de la terapia con multiples drogas (MDT), los pacientes que eran clínicamente inactivos, baciloscopicamente negativos en los extendidos de linfa cutánea, y que se habían tratado con monoterapia con dapsona cuando menos durante 5 años (pacientes paucibacilares) o durante 10 años (pacientes multibacilares), eran dados de alta y liberados del tratamiento.Se hizo un análisis del número de recaídas observado en 1081 pacientes paucibacilares (PB) y 1123 pacientes multibacilares (MB) que habían sido dados de alta en Addis Ababa y en 2 distritos rurales supervisados por el programa de control de la lepra del All África leprosy and Rehabilitation Training Center (ALERT). Durante un periodo promedio de 6.6 años después de haberse liberado del tratamiento con dapsona, se diagnosticaron 44 recaídas entre los pacientes PB y 148 recaídas entre los pacientes MB. El grado global de recaída fue de 4.1% o 7.2 por 1000 pacientes-años para los pacientes PB y del 13.2% y 24.8, respectivamente, para los pacientes MB. El grado anual de recaída en los pacientes PB no varió significativamente de año a año. Sin embargo, el índice de recaída para los pacientes MB fue significativamente menor entre el quinto y el séptimo año después de haber suspendido el tratamiento y mayor durante los primeros 4 años. Basados en los hallazgos clínicos, hubo una fuerte sospecha de recaída con bacilos resistentes a la dapsona en el 40% de las recaídas MB. Se concluye que el grado de recaída para los pacientes PB es aceptable. Sin embargo, el grado de recaída para los pacientes MB se considera muy elevado. Por esta razón, se recomienda administrar a todos los pacientes MB, incluyendo a aquellos que han estado en tratamiento con dapsona durante mucho tiempo y que se han declarado clínicay bacteriológicamente negativos, un tratamiento de 2 años con MDT.

When dapsone monotherapy was the only treatment available for routine field conditions, there was great reluctance to release patients from treatment because some patients might relapse. This was considered a failure on the part of the health services. In addition, because patients were not examined regularly, the recommended criteria for release of patients-continuation of dapsone for a defined period after attainment of clinical or clinical and bacteriological inactivity-often could not be applied.

Since the widespread introduction of the sulfones in 1947, several recommendations for the duration of treatment have been given. In particular, for multibacillary patients the recommended period of treatment has been extended gradually. In 1966 a WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy recommended that lepromatous patients becoming clinically inactive and smear negative should be continued on treatment for 5 years (35). In 1970 a WH O Expert Committee recommended continuation of regular treatment for 1 ½ years for tuberculoid patients, 3 years for indeterminate patients, and at least 10 years for borderline and lepromatous patients following attainment of clinical and bacteriological inactivity (36). In 1980 it was advised that lepromatous patients should continue dapsone for life until more evidence was available on the efficacy of combined therapy in reducing or eliminating relapses (37).

At the end of 1983 when the "Manual for Implementation of Multiple Drug Therapy in Ethiopia" was written, it was decided to reserve multiple drug therapy (MDT) for patients with active disease (18). Criteria for release from treatment (RFT) of patients who had been treated with dapsone for long periods were defined and applied. An analysis of relapses in self-reporting patients was made in one urban and two rural districts of the Shoa Region of Ethiopia.

In this paper the findings in paucibacillary (PB) and multibacillary (MB) patients during a maximum period of 7 years after stopping dapsone are presented.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The leprosy control division of the All Africa Leprosy and Rehabilitation Training Center (ALERT) is responsible for leprosy control in the Shoa Region, the central region of Ethiopia. The region is divided into 11 rural districts and the city of Addis Ababa. It covers about 85,000 sq. km. with an estimated population of 11 million (1989). An analysis was made of the relapses among self-reporting patients who had been released from dapsone in Addis Ababa and in two surrounding rural districts. This area covers about 35,000 sq. km. with an estimated population of 3.4 million, of whom 50% reside in Addis Ababa (1989).

The area was selected for the following reasons: a) It was the first area where, prior to implementation of MDT, a large-scale release of patients on dapsone was carried out. b) During 1987 B. H. Hansen did a detailed study on relapses which had been diagnosed in this area during a maximum period of 3 ½ years after release from treatment (RFT) (Hansen, unpublished report, 1988). Her findings will be compared with those observed after an extension ofthe period after stopping treatment for an additional 3 ½ years, c) During 1974, 678 patients had been released from dapsone in Addis Ababa (29). The relapse rates in these patients will be compared with those observed in patients who were released about 10 years later, d) Of the patients released since the end of 1983, past clinical and bacteriological findings had been well documented, e) Over 80% of the relapses were diagnosed in the hospital where, in addition to clinical and bacteriological examinations, an ophthalmological examination was done and skin and/or nerve biopsies were examined.

Most of the patients in the study area have easy access to the leprosy control services. From the records it was estimated that 60%-70% of the patients attended at least once per year during the first 3 years after release from dapsone. During the fifth year 30%-40% ofthe patients attended. In other districts ofthe control area only about 30% of the patients attended for follow-up examinations during the third year after release from dapsone.

At the end of 1983, a clinical and bacteriological review of all patients on dapsone was started. The review was done by the leprosy control supervisors and senior staff of the leprosy control division. Based on past records patients who, according to the Madrid classification, had been classified as "B" were reclassified either as borderline tuberculoid (BT) or borderline lepromatous (BL) leprosy. In case of doubt the patients were classified as BL.

Indeterminate, tuberculoid (TT) and BT patients who were clinically inactive, had negative skin smears, and had collected dapsone for 200 weeks or more during a period of 5-10 years, or had been on dapsone for over 10 years, regardless of the regularity of attendance, were released from treatment.

BL and lepromatous (LL) leprosy patients who were clinically inactive, had negative skin smears in two sets of skin smears (which had to be taken within a period of 2-6 months) were released from treatment if: a) they had attended regularly for at least 10 years, regular attendance being defined as a cumulative attendance rate of at least 75%; or b) they had been on treatment for more than 15 years, either according to the total cumulative attendance or from history, regardless of the regularity of attendance. During the review for release from dapsone, skin smears were routinely taken from four sites: two earlobes, an elbow, and a knee.

In the clinics of Addis Ababa, a review and release of the patients was carried out during a few months' campaign which was almost completed when MDT was introduced in March 1984. In the rural districts the assessment and release from dapsone was done gradually and continued after MDT was introduced in May 1984.

Over the years the patients had been treated with different dosages of dapsone: a) Until 1974 the dosage of dapsone was gradually, over a period of 3-6 months, increased to 300 mg once weekly for indeterminate and T patients and to 200 mg once weekly for B and L patients. If a leprosy reaction occurred, dapsone was discontinued and gradually increased again after the reaction had subsided, b) From 1974 to 1976 all classifications of leprosy were given 300 mg dapsone once weekly immediately from the start of treatment, c) Since 1976 all classifications of leprosy were treated with a daily dose of 100 mg dapsone immediately from the start of treatment.

At the time of their release, the patients were told that there is a chance the disease will re-occur. They were instructed to attend the service any time they observed new signs of the disease and once yearly for a period of 5 years for follow-up examinations. Patients who attended were clinically examined. Of former PB patients who presented with suspect new signs of the disease and of all former MB patients skin smears were examined. Patients who did not attend for follow-up examinations were not traced.

Because over 90% of the patients presented themselves with signs of leprosy in the past, it was expected that they would also attend the service if they noticed new signs of the disease. This was confirmed by Hansen in her study on relapses in the same group of patients presented in this paper. Among the 2204 patients who were released from dapsone 125 self-reporting relapses (5.7%) were diagnosed during the first 3 ½ years after stopping treatment. A random sample of 135 of all released patients who had not been diagnosed with a relapse was examined during the third year after stopping dapsone. In these patients only one unreported relapse was diagnosed (0.7%; 95% confidence interval 0-2.2%) (Hansen, unpublished report, 1988).

During 1984, the senior staff of ALERT defined criteria for relapse after release from treatment (5). The presence of one or more of the following signs was considered evidence for relapse: a) new skin lesions; b) new activity in previously existing skin lesions; c) positive skin smears, with a bacterial index (BI) of 2 or more in one or more sites, observed in two sets of skin smears, in the presence or absence of new skin lesions; d) new nerve function loss detected by sensation testing (ST) and/or voluntary muscle testing (VMT) in hand(s) and/or foot(feet) and/or tenderness in a nerve that was normal at the time of release from treatment; e) histological evidence of relapse in skin or nerve biopsy; and f) lepromatous activity in the eye(s).

Because it was decided that a MB relapse should be diagnosed on clinical and bacteriological grounds, preferably supported by histological findings and all patients diagnosed with a relapse should be treated with MDT, a mouse foot-pad inoculation to confirm a MB relapse and to establish the sensitivity of the bacilli to dapsone was not done. Patients suspected of having a relapse and residing in Addis Ababa were referred to the ALERT hospital for confirmation of the diagnosis. Based on clinical signs and/ or the results of skin-smear examinations, the diagnosis of patients attending the rural clinics was made by the leprosy control staff. In case of doubt these patients were referred to the ALERT hospital for further examinations.

For all patients diagnosed with a relapse the supervisors have to fill in an individual report form which gives a summary of past and new findings. In order to assess whether all relapses had been reported, the record cards of all patients who had been on antileprosy treatment in the area since the end of 1983 were scrutinized during early 1990 and early 1991. Details of the clinical, bacteriological, and histological findings were obtained from patient record cards and hospital files.

The annual rates of self-reporting relapses during the first to the seventh year after release from treatment were calculated per 1000 patient years after release from treatment. Patients released during a period were considered released in the middle of that period. In calculating the number of patient years all patients were included, while an annual reduction for death and leaving the control area of 3% for PB patients and 4% for MB patients was made. These percentages were, as averages, observed during the period 1973-1983 for patients on dapsone in the study area (2).

RESULTS

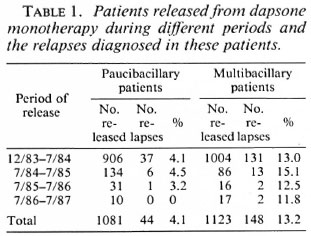

By early 1991 individual reports were available for 174 patients diagnosed with a relapse. In addition, 51 relapses were obtained from patient record cards. Thirtythree relapses were excluded because they had been diagnosed in patients who were released before the end of 1983 (29 relapses), who restarted treatment after defaulting (2 patients), or who had been diagnosed with a relapse after release from MDT (2 patients). Therefore by early 1991, 192 relapses had been diagnosed among patients who were released from dapsone since the end of 1983.

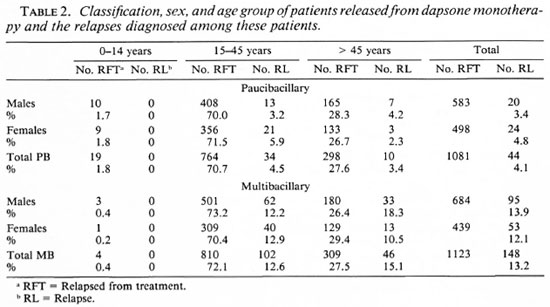

The numbers of PB and MB patients who had been released from dapsone during subsequent periods and the number of relapses which have been diagnosed among them are given in Table 1. Table 2 presents the classification, sex, and age group of the patients released from dapsone and the relapses diagnosed among these patients. Age was found quite unreliable. Because patients often do not know their age, the staff had to make the best possible estimate, and therefore no further subdivision in age groups was made. No significant differences in the relapse rates related to sex or to age group were found (all p > 0.05).

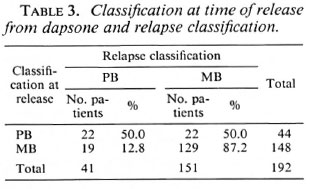

One-hundred-fifty-seven relapses were classified initially as MB and 35 as PB. Based on the assessment of clinical and bacteriological findings, seven of the relapses classified as MB were reclassified as PB. These patients had a few skin lesions characteristic for PB leprosy, while skin smears were negative. Because they had been classified as MB in the past, it was decided to classify the relapse as MB also. In addition, one relapse classified as PB was reclassified as MB. In this patient an eye leproma was observed by the ophthalmologist, while skin smears were negative. Therefore there were 151 MB relapses and 41 PB relapses.

The classification at the time of release from dapsone versus the relapse classification is presented in Table 3. Records of nine patients, classified as PB at the time of their release and diagnosed with a MB relapse, confirmed or strongly suggested MB leprosy in the past. Five of these patients had multiple skin lesions and positive skin smears. Four patients had multiple, ill-defined skin lesions with multiple nerve enlargement and a negative lepromin test, while skin smears were negative (two patients) or skin-smear results were not available (two patients). Of the 44 relapses among PB patients, 30 patients (68.2%) had attended regularly for 5 years or more, 12 (27.3%) had been on treatment for over 10 years, and for 2 patients (4.5%) the treatment period was not recorded.

Clinical and bacteriological records of the 19 patients who were classified as MB at the time of their release from dapsone, and who relapsed with PB leprosy, confirmed MB leprosy in the past. Of the 148 relapses among MB patients, 80 patients (54.1 %) had attended regularly over 10 years or more, 58 (39.2%) had been on treatment for over 15 years, and for 10 patients (6.8%) the attendance was either not recorded (7 patients) or they had been on treatment for less than 10 years (3 patients).

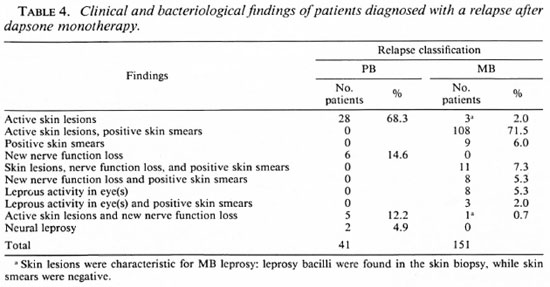

Table 4 gives the clinical and bacteriological findings of the patients who were diagnosed with a relapse. Of the 151 patients who were diagnosed with a MB relapse in 119 patients (78.8%) either skin lesions and positive skin smears were observed (108 patients) or skin lesions, positive skin smears, and new nerve function loss (11 patients). The records of 14 of these 119 patients (11.8%) showed histoid skin lesions. These lesions often appeared in sites (loins, lower back, neck) which are usually not affected by leprosy. In addition, 45 patients (37.8%) presented with one to a few skin lesions. The clinical presentations of these 59 patients appear similar to what had been observed among patients who, due to dapsone resistance, developed new activity of the disease while on dapsone. The remaining 60 patients (50.4%) presented with multiple skin lesions.

Lepromatous activity in the eye, in the presence or absence of positive skin smears, was observed in 1 1 patients (7.3%): (epi)scleritis in 5 patients, iritis in 4 patients, and leproma in 2 patients. The clinical presentation of an eye leproma is highly suspicious for relapse with dapsone-resistant bacilli. The BI of the 139 patients with positive skin smears ranged from 2+ to 6+ on the logarithmic scale as the highest BI of four sites; 113 of them (81.3%) had a BI of 3 + , 4 + , or 5 + . The patients in whom, on clinical signs, dapsone resistance was suspected had a BI of 4+ or more in the lesions. The morphological index (MI) ranged from 0% to 23%. Of the 9 patients with positive skin smears only, 7 had a BI of 2+ and 2 had a BI of 3 + ; the Mis were reported as 0%.

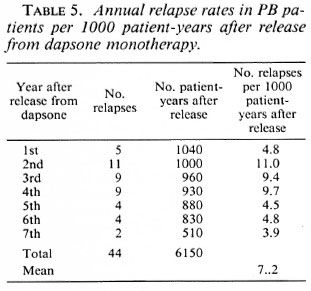

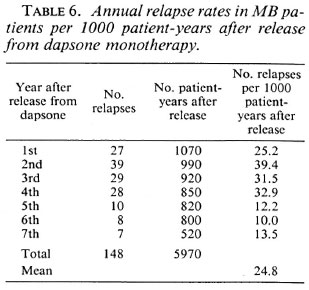

The annual relapse rates per 1000 patient years during the first to seventh year after release from dapsone are given in Tables 5 and 6. The year is that during which the relapses were diagnosed. Because some patients reported that they observed new signs of the disease a few to several months before they attended the clinic, this year may not always be the same year in which the relapse occurred. For PB patients the relapse rate seems highest during the second to fourth year after stopping dapsone; however, the difference with following years does not reach statistical significance (χ2 = 6.62, p = 0.32). For MB patients the relapse rate is significantly lower during the fifth to seventh year after stopping dapsone as compared with the first 4 years (χ2 = 28.18, p < 0.001). For relapses in PB patients the mean period between stopping treatment and the diagnosis of relapse was 35.8 months (median = 34 months). For relapses in MB patients the mean period was 31.2 months (median = 27 months).

DISCUSSION

In the ALERT leprosy control program, as in many other leprosy control programs, there had been no systematic approach to the release of patients on dapsone monotherapy. Since 1969 and until 1982, with the exception of 1974, during any year not more than 1% of the patients on dapsone were released (1). During 1974, 678 patients were released from dapsone in Addis Ababa, representing 17.5% of the patients on dapsone on the area. The reason for the decision to release these patients could not be traced. Because of the high relapse rates which were observed among these patients (16.5% in PB patients and 32.4% in MB patients during the first 3 ½ years after stopping treatment 29), the ALERT staff became very reluctant to continue to release patients from dapsone. Further, the outcome of studies on secondary and primary dapsone resistance showed the shortcomings of dapsone monotherapy. From studies carried out in Addis Ababa, the prevalence of dapsone resistance was estimated at 190 per 1000 lepromatous patients in 1978 (24, 25).

Nevertheless, since the end of 1983 several thousand patients (about 5000 PB patients and 2500 MB patients) were released from dapsone in the ALERT leprosy control program. Because the low-dosage treatment was considered the main reason for the high relapse rate in PB patients who were released during 1974, it was decided to release clinically and bacteriologically inactive PB patients who had been prescribed full-dose daily dapsone for at least 5 years.

The major considerations in this decision to release MB patients were: a) the patients had been treated with full-dose daily dapsone since 1976; low-dosage dapsone was considered one of the reasons for the high relapse rate in the patients who were released during 1974. b) following the introduction of full-dose daily dapsone a steep decline (from 3% to 1%) was observed in the incidence of secondary dapsone resistance (31). Therefore, the problem of dapsone resistance was considered much less under full-dose treatment compared with low-dose dapsone. c) the limited resources which were available for MDT drugs made it necessary to reserve the treatment for certain categories of patients.

Since the introduction of the sulfones during the 1940s, several studies have been carried out on relapses following discontinuation of the treatment. Publications give a wide range in the observed relapse rates. For patients at the tuberculoid side relapse percentages of < 1% to > 17% are reported (Hansen, unpublished report, 1988, and 7. 9, 12, 15-17, 19, 22, 27, 29, 30). The reported percentage of relapses in patients at the lepromatous side ranges from 2% to > 30% (Hansen, unpublished report, 1988, and 7, 8, 14, 17, 20, 21, 26, 28, 29, 33). In some studies relapse rates per 1000 patient-years of follow up are reported. These range from 5.3 to 21.6 per 1000 patient-years of follow up for PB patients (Hansen, unpublished report, 1988, and 5, 15, 22) and from 10.4 to 30.7 for MB patients (Hansen, unpublished report, 1988, and 8, 33).

The various studies are difficult to interpret and to compare. There is much variation in the dapsone dosage, the method of classification of the patients, the duration of treatment, the period and method of follow up after stopping treatment, and the criteria for the diagnosis of relapse. During recent years some well-documented studies have been published. When relapse rates reported from these studies are compared with those observed in the ALERT leprosy control program, the following picture emerges.

Relapses in PB patients. Hansen (unpublished report, 1988) studied relapses during a maximum period of 3 ½ years after release from treatment in the same group of patients reported in this paper. In the 1081 PB patients 22 relapses (2.0%) were diagnosed, giving a relapse rate of 6.7 per 1000 patient-years after release from treatment. In her analysis the number of patientyears was not corrected for estimated death and those who left the control area. After an extension of the follow-up period for an additional 3 ½ years, the relapse percentage doubled to 4.1%, and the estimated relapse rate per 1000 patient-years after stopping treatment was 7.2.

Jesudasan, et al. observed, during a 3-year period of active follow up of the patients, 3% relapses in 1701 PB patients or a relapse rate of 9.7 per 1000 patient-years at risk (15).

A much higher relapse rate was observed by Touw-Langendijk, et al. in patients released from dapsone in Addis Ababa. In 204 PB patients who had been treated with dapsone for at least 5 years and who were released during 1974, they reported 15.2% relapses (29). These relapses were observed in self-reporting patients during the first 3 ½ years after release from treatment. With the same duration of treatment, the period and method of follow up, their percentage of relapses is very significantly higher than that observed by Hansen (χ2 = 117.4, p < 0.001). The main reason for this difference is most probably the low-dose dapsone treatment which was used before 1974.

Several investigators have reported a maximum relapse rate 2 years after stopping dapsone (12, 15, 29, 30); while others did not find a variation of relapse rate with time (19, 22). A significant variation of the relapse rate with time was not observed in the present material.

Some investigators reported that 50% or more of the relapses occur within the first 2-3 years after release from treatment (19, 23, 29). In a study on the incubation time of relapses in PB patients, only 3 of 31 relapses occurred more than 6 years after stopping treatment (23). Similar results in PB patients released in the ALERT leprosy control program would mean that although some relapses may still occur more than 7 years after release from dapsone, these will be very few.

Some patients may have suffered from a late reversal reaction rather than from a relapse. Most reversal reactions do occur within the first year after starting effective treatment, although they can occur even during the fourth year (6, 32). Because the patients had been on dapsone for at least 5 years, the chance of a late reversal reaction after stopping treatment was considered very small.

Although the relationship between relapse and pregnancy/lactation was not studied, no significant differences in relapse rates were observed in females of child-bearing age (15-45 years) compared to those older than 45 years, or between females and males. Duncan, e l al. in their study on leprosy and pregnancy reported an increased risk of relapse during pregnancy and lactation (10, 11).

Possible causes for PB relapse are: a) poor compliance of patients with drug intake. Regularity of attendance for treatment does not mean that patients are regular in taking the dapsone. This has been observed in several studies. Ellard, et al. found that only 60% of 295 patients who were studied in Addis Ababa ingested the prescribed dapsone regularly (13). In studies which were carried out in the ALERT leprosy control program just before implementation of MDT, it was found that the urines of 29% of 843 patients who had attended regularly were negative for the presence of dapsone. b) undertreatment due to incorrect classification. Incorrect classification in the past was confirmed in five patients who were diagnosed with a MB relapse and was likely in four patients, c) incorrect duration of treatment. Except for two patients whose treatment periods were not known, all patients had been prescribed full-dose daily dapsone for at least 5 years.

A relapse rate of 4.1% or 7.2 per 1000 patient-years, during an average period of 6.6 years after release from treatment, should be considered acceptable. Because relapses were observed among self-reporting patients, not all relapses may have been diagnosed. However, based on the result of the examination of a random sample of the patients, these are probably very few.

This study shows that dapsone prescribed at a full daily dose for 5 years will cure most PB patients. Whether comparable results can be obtained with a shorter period of fulldose daily dapsone is not known.

Although most PB patients will be cured with dapsone, dapsone monotherapy has several disadvantages compared with MDT:

a) While the vast majority of PB patients complete the course of MDT, the proportion of patients who complete 5 years of dapsone is substantially lower. In the ALERT leprosy control program it was observed that over 90% of PB patients completed the six doses of MDT within 9 months (unpublished data and 3). It was estimated that during the days of dapsone monotherapy at most 60% of the patients completed 5 years of dapsone treatment (11). In addition, the compliance with the unsupervised intake of dapsone was significantly higher on MDT than on dapsone monotherapy. The urine spot test for the presence of dapsone gave 84% positive results in 2305 urines of PB patients on MDT, compared with 71% positive urines in 843 patients on dapsone monotherapy (χ2 = 62.5, p < 0.001; unpublished data).

b) Although the relapse rate after stopping dapsone was low, the relapse rate after release from MDT was found to be lower. In 3065 PB patients who were released from MDT, 16 relapses for which there was strong evidence for the diagnosis were observed during an average period of 6.1 years after stopping MDT (unpublished data). This is a relapse rate of 0.5% or 1.0 relapses per 1000 patient-years after stopping MDT. With about the same average period after stopping treatment, the relapse rate after MDT is significantly lower than the relapse rate after dapsone monotherapy (χ2 = 70.6, p < 0.001).

c) Treatment with dapsone for 5 years is more expensive than treatment with MDT for 6 months. If only expenses for drugs are taken into consideration, 5 years of dapsone is about four times as expensive as 6 months of MDT (approximately US$8 and US$2, respectively). Therefore, treatment with MDT is definitely much more cost effective than treatment with dapsone monotherapy.

Relapses in MB patients. Hansen, who studied relapse in the same group of 1123 MB patients, reported 103 relapses (9.2%) or 30.7 relapses per 1000 patient-years after release from treatment, during a maximum period of 3 ½ years after stopping dapsone (unpublished report, 1988). The latter rate was not corrected for estimated death or for leaving the control area. After extension of the period after release for an additional 3 ½ years, the relapse rate was 13.2% or 24.8 relapses per 1000 patient-years after release from treatment.

Waters, et al., who studied relapses in 362 institutionalized patients, reported 6.9% relapses or a relapse rate of 10.4 per 1000 patient-years during a period of active follow up of 8-9 years (33). Because their patients had been treated for about 20 years with fully supervised dapsone, this relapse rate is most probably the lowest which can be obtained with dapsone monotherapy. With almost the same period after release from treatment, the relapse rate observed in the ALERT leprosy control program is significantly higher (χ2 = 10.47, p = 0.001).

Touw-Langendijk, et al. reported 32.4% relapses during the first 3 ½ years after release from dapsone in 37 MB patients treated for at least 10 years after they had attained clinical and bacteriological inactivity 29). With the same period and method of follow up, their relapse rate is significantly higher than that observed by Hansen in MB patients who were released about 10 years later (χ2 = 19.2, p < 0.001).

In a longitudinal study on relapses in MB patients treated with dapsone monotherapy, Cartel, et al., using the lifetable method, observed a cumulative relapse probability of 0.38 ± 0.11 over a total period of 36 years. They concluded that roughly one third to one half of the MB patients treated with dapsone monotherapy would relapse if still alive 36 years after bacteriological negativity (8). Waters, et al. reported that the risk of relapse did not vary significantly from year to year (33).

In the current study, the relapse rate was significantly lower during the fifth to seventh year after stopping dapsone as compared with the first 4 years. The diagnosis of relapse is doubtful in the nine patients who had positive skin smears only. Although the first signs of relapse may be an increase in the BI only, this should be associated with the finding of raised Mis. Because this was not observed, the finding of positive skin smears may well have been caused by chance sampling in the selection of smear sites. Also, for MB patients no significant differences in the relapse rates were observed in females of 15-45 years (compared to those older than 45 years) or between females and males. Duncan, et al. reported an increased risk of relapse during pregnancy and lactation (10,11).

Major causes of relapse in MB patients who have been treated with dapsone monotherapy are:

a) Poor compliance with self-administration of dapsone. This is most probably the main reason for the significantly higher relapse rate in patients who were released from the ALERT leprosy control program compared with the findings by Waters, et al.

b) Low-dose dapsone. This is most probably the main reason for the significantly higher relapse rate observed by Touw-Langendijk, et al. in the patients who were released during 1974, as compared with patients who were released about 10 years later.

c) Dapsone resistance. Although dapsone resistance was not studied, many patients may have relapsed with dapsone-resistant bacilli. Based on clinical findings there was strong suspicion of dapsone-resistant relapse in 40.4% of the 151 patients who were diagnosed with a MB relapse. Also, patients who presented with multiple skin lesions may have relapsed with dapsone-resistant bacilli. During the review before release from treatment, early signs of new activity of the disease may have been missed in part of the patients, while skin smears taken from routine sites were negative. Relapses with dapsone-resistant bacilli, which were confirmed by mouse foot pad tests, have been reported by Waters, et al. (33).

d) Persistent Mycobacterium leprae. Persisters may survive for many years. Waters, et al. have isolated dapsone-sensitive persisters in patients who had been treated with dapsone given supervised for 10 years or more (34). Neither dapsone nor the other available leprosy drugs are able to kill persistent M. leprae. In his studies on relapses with proven dapsone resistance, Waters demonstrated that relapse after stopping dapsone due to microbacterial persistence is most probably of much lesser risk than that of relapse due to dapsone resistance (32). Even if some of the patients diagnosed with a relapse did not suffer from a genuine relapse, the relapse rate in MB patients should be considered too high. In addition, because the maximum period after stopping dapsone was only 7 years, more relapses can be expected. Cartel, et al. reported that of 36 relapses only 9 (25%) developed within the first 8.5 years (8).

The finding in the ALERT leprosy control program illustrates the necessity of treating all MB patients, including those who have been on long-term treatment with dapsone and have become clinically and bacteriologically inactive, with a course of MDT. While a proportion of the relapses after dapsone monotherapy will be associated with the emergence of dapsone-resistant M. leprae, relapses after MDT are most likely due to the multiplication of persistent bacilli which are fully sensitive to the drugs.

Rather than waiting until patients present with signs of relapse, it is strongly recommended to administer a 2-year course of MDT to MB patients who have been released from dapsone. It often may not be feasible to trace these patients actively. However, a start could be made with patients who attend for follow-up examinations or for care of complications of the disease.

Acknowledgment. I should like to express my thanks to the ALERT leprosy control supervisors who recorded and collected the data, and to Prof. Dr. A. S. Muller for his comments and suggestions.

REFERENCES

1. Alert. Annual reports 1969-1982. Addis Ababa: Armauer Hansen Research Institute.

2. Alert. Annual reports 1973-1982. Addis Ababa: Armauer Hansen Research Institute.

3. Alert. Annual reports 1984-1989. Addis Ababa: Armauer Hansen Research Institute.

4. Alert. Annual report 1985. Addis Ababa: Armauer Hansen Research Institute.

5. Alert."Standardization of hospital records and procedures." Addis Ababa: Armauer Hansen Research Institute, 1984.

6. Becx-Bleumink, M . and Berhe, D. Occurrence of reactions, their diagnosis and management in leprosy patients treated with multidrug therapy, experiences in the leprosy control program of the All Africa Leprosy and Rehabilitation Training Center (ALERT) in Ethiopia. Int. J. Lepr. 60(1992)173-184.

7. Browne, S. G. Relapses in leprosy; Uzuakoli Settlement, 1958-1964. Int. J. Lepr. 33(1966)273-279.

8. Cartel, J.-L., Boutin, J.-P., Spiegel, A., Plichart, R. and Roux, J.-F. Longitudinal study on relapses of leprosy in Polynesian multibacillary patients on dapsone monotherapy between 1946 and 1970. Lepr. Rev. 62(1991)186-192.

9. Davey, T. F. "Release from control" in leprosy. Lepr. Rev. 49(1978)1-6.

10. Duncan, M. E., Melsom, R., Pearson, J. M. H. and Ridley, D. S. The association of pregnancy and leprosy: 1. New cases, relapse of cured patients and deterioration in patients on treatment during pregnancy and lactation -results of a prospective study of 154 pregnancies in 147 Ethiopian women. Lepr. Rev. 52(1981)245-262.

11. Duncan, M. E., Pearson, J. M. H., Ridley, D. S., Melsom, R. and Bjune, G. Pregnancy and leprosy: the consequences of alterations of cell mediated and humoral immunity during pregnancy and lactation. Int. J. Lepr. 50(1982)425-435.

12. Ekambaram, Duration of treatment for disease arrest on non-lepromatous cases and relapse rate in these patients. Lepr. Rev. 50(1979)297-302.

13. Ellard, G. A., Pearson, J. M. H. and Haile, G. S. The self-administration of dapsone by leprosy patients in Ethiopia. Lepr. Rev. 52(1981)237-243.

14. Erickson. P. T. Relapse following apparent arrest of leprosy by sulphone therapy. Int. J. Lepr. 19(1951)63-74.

15. Jesudasan, K., Christian, M. and Bradley, D. Relapse rates among nonlepromatous patients released from control. Int. J. Lepr. 52(1983)304-310.

16. Kandasamy, V. Relapse in leprosy in a mass control scheme. (Abstract) Int. J. Lepr. 36(1968) 657. 17.

17. Lowe, J. Chemotherapy of leprosy; late results of treatment with sulphone, and with thiosemicarbazonc. Lancet 2(1954)1065-1068.

18. Manual for Implementation of Multiple Drug Therapy (MDT) in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: ALERT, 1983. 19.

19. Neelan, P. N. Relapse in non-lepromatous leprosy with dapsone therapy; relationship to treatment status after inactivation. Lepr. India 51(1979)120-121.

20. Noordeen, S. K. Relapse in lepromatous leprosy. Lepr. Rev. 42(1971)43-48.

21. Noordeen, S. K. Relapse in lepromatous and borderline leprosy under dapsone therapy. Lepr. India 51(1979)119-120.

22. Pandian, T. D., Sithambaram, M., Bharathi, T. and Ramu, G. A study of relapse in non-lepromatous and intermediate groups of leprosy. Indian J. Lepr. 57(1985)149-157.

23. Pattyn, S. R. Incubation time of relapses after treatment of paucibacillary leprosy. Lepr. Rev. 55(1984)115-120.

24. Pearson, J. M. H. Dapsone-resistant leprosy. Lepr. Rev. Special Issue (1983)85S-89S.

25. Pearson, J. M. H., Ross, W. F. and Rees, R. J. W. DDS resistance in Ethiopia; a progress report. Int. J. Lepr. 44(1976)140-142.

26. Qualiatto, R., Bechelli, L. M. and Marques, R. M. Bacterial negativity and reactivation (relapse) of lepromatous outpatients under sulfonc treatment. Int. J. Lepr. 38(1970)250-263.

27. Ramu, G. and Ramunujam, K. Relapses in borderline leprosy. Lepr. India 46(1974)21-25.

28. Rodriguez, J. N. Relapses after sulfone therapy in leprosy of the lepromatous type. Int. J. Lepr. 26(1958)305-312.

29. Touw-Langendijk, E. M. J. and Naafs, B. Relapse in leprosy after release from control. Lepr. Rev. 50(1979)123-127.

30. Vellut, C, Lechat, M. F. and Misson, C. B. Tuberculoid relapses. Proceedings of the XI International Leprosy Congress, 1978, Mexico City. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica, 1980, pp. 293-298.

31. Warndorff-van Diepen, T., A redath, S. P. and Mengistu, G. dapsone-resistant leprosy in Addis Ababa: a progress report. Lepr. Rev. 55(1984)149-157.

32. Waters, M. F. R. The chemotherapy of leprosy. In: The Biology of the Mycobacteria. Volume 3; Clinical Aspects of Mycobacterial Diseases. Ratledge, C, Stanford, J. and Grange, J. M., eds. London: Academic Press, 1989, pp. 406-474.

33. Waters, M. F. R., Rees, R. J. W., L aing. A. B. G., K ho, K. F., Meade. T. W., Parikshah, N. and North, W. R. S. The rate of relapse in lepromatous leprosy following completion of twenty years of supervised sulphone therapy. Lepr. Rev. 57(1986)101-109.

34. Waters, M. F. R., Rees, R. J. W., McDougall, A. C. and Weddell, A. G. M. Ten years of dapsone in lepromatous leprosy: clinical, bacteriological and histological assessment and the finding of viable bacilli. Lepr. Rev. 45(1974)288-298.

35. WHO Expert Committee o n Leprosy. Third report. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1966. Tech. Rep. Ser. 319.

36. WHO Expert Committee o n Leprosy. Fourth report. Geneva: World Health Organization. 1970. Tech. Rep. Serv. 459.

37. World Health Organization. A Guide to leprosy control. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1980.

M. Becx-Bleumink. M.D., D.T.P.H., All Africa Leprosy and Rehabilitation Training Center (ALERT), Armauer Hansen Research Institute (AHRI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Reprint request to Dr. Becx-Bleumink, Plasweg 15, 3768 AK Soest, The Netherlands.

Received for publication on 23 October 1991.

Accepted for publication in revised form on 7 January 1992.