- Volume 60 , Number 3

- Page: 340–52

Sensitization potential and reactogenicity of BCG with and without various doses of killed Mycobacterium leprae

ABSTRACT

A study was conducted in 997 individuals in two villages in south India to find the acceptability and sensitizing effect of the antileprosy combination vaccine of BCG plus killed Mycobacterium leprae (KML). Three preparations of the combination, BCG 0.1 mg + 6 x 108 KML (I), BCG 0.1 mg + 5 x 107 KML (II), and BCG 0.1 mg + 5 x 106 KML (III), along with BCG 0.1 mg (IV), and normal saline (V), were used in the study. Each individual received one of the above five preparations by random allocation. They were also tested with Rees' M. leprae soluble skin-test antigen (MLSA) and lepromin-A, both at intake and 12 weeks after vaccination. Reactions to Rees' MLSA were measured after 48 hr; those to lepromin-A after 48 hr and 3 weeks. The character and size of the local response at the vaccination site were recorded at 3, 8, 12, 15, and 27 weeks after vaccination. The mean sizes of postvaccination sensitization to both Rees' MLSA and lepromin-A in the vaccine groups were significantly larger than those in the normal saline group, clearly demonstrating the ability of the vaccines to induce sensitization as measured by responses to the two skin tests. The sensitizing effect was the highest following vaccination with vaccine I. It was not significantly different for vaccines II, III, and IV, although, generally, a dose-response effect was observed. The sensitizing effect attributable to the vaccine was more clearly seen in children than in adults. The above conclusions were the same irrespective of which results were considered, reactions to Rees' MLSA or Fernandez or Mitsuda reactions to lepromin-A. A significant finding of the study was that at intake the Mitsuda reactions provided a measure of sensitizing effect due to vaccine. The healing of vaccination lesions was uneventful. In more than 90% of vaccinated individuals, the lesions had healed by the 12th week in vaccine groups II, III, and IV, and by the 15th week in vaccine group I. The results showed that vaccination with BCG or combination vaccines was equally safe in individuals with or without previous BCG scars. Thirteen persons, aged 10 years or older, developed suppurative lymphadenitis around the 8th week (7 in vaccine group I, 3 each in vaccine groups II and III). However, healing was prompt after drainage in these individuals.RÉSUMÉ

Une étude a été réalisée chez 997 personnes dans deux villages du sud de l'Inde pour analyser l'acceptabilité et l'effet sensibilisateur du vaccin antilépreux combinant le BCG et du Mycobacterium leprae tué (KML). Trois préparations de la combinaison, BCG 0.1 mg + 6 x 108 KML (I), BCG 0.1 mg + 5 x 107 KML (II), et BCG 0.1 mg + 5 x 106 KML (III), ainsi que du BCG 0.1 mg (IV), et une préparation saline normale (V) ont été utilisées dans l'étude. Chaque personne a reçu l'une des cinq préparations citées plus haut par attribution aléatoire. Ils furent également testés avec l'antigène cutané soluble de M. leprae de Rees (MLSA) et avec lépromine-A, tous deux administrés au moment et 12 semaines après la vaccination. Les réactions vis-à-vis du MLSA de Rees ont été mesurées après 48 heures; celles à la lépromine-A après 48 heures et 3 semaines. La caractère et la taille de la réponse locale au site de vaccination ont été enregistrés à 3, 8, 12, 15, et 27 semaines après la vaccination. Les tailles moyennes de la sensibilisation post-vaccinale au MLSA de Rees et à la lépromine-A dans les groupes des vaccinés étaient significativement plus grandes que dans le groupe ayant reçu la solution saline normale, démontrant clairement la capacité des vaccins de produire une sensibilisation ainsi que mesurée par les réponses aux deux test cutanés. L'effet sensibilisateur était le plus grand après la vaccination avec le vaccin I. II n'était pas significativement différent pour les vaccins II, III, et IV, bien que généralement une relation dose/effet était observée. L'effet sensibilisant attribuable au vaccin était vu plus clairement chez les enfants que chez, les adultes. Les conclusions ci-dessus étaient les mêmes quels que soient les résultats considérés, qu'il s'agisse des réactions au MLSA de Rees ou aux réactions de Fernandez ou de Mitsuda à la lépromine-A. Une observation significative de l'étude était que les réactions de Mitsuda réalisées au moment de l'enrôlement fournissaient une mesure de l'effet sensibilisateur au vaccin. La guérison des lésions vaccinales se déroula sans problème. Dans plus de 90% des personnes vaccinées, les lésions étaient guéries à la douzième semaine dans les groupes de vaccination II, III et IV et à la quinzième semaine dans le groupe de vaccination I. Les résultats ont montré que la vaccination avec le BCG ou les vaccins de combinaison était également sûre chez des personnes avec ou sans cicatrice préalable de BCG. Seize personnes, âgées de 10 ans ou plus ont développé une lymphadénite suppurative aux environs de la 8ème semaine (7 dans le groupe I, 3 chacuns dans les groupes II et III). Cependant, la guérison était rapide chez ces personnes après drainage.RESUMEN

Se realizó un estudio en 997 individuos de 2 poblaciones del sur de la India para encontrar la aceptabilidad y el efecto sensibilizante de la vacuna preparada con BCG y con Mycobacterium leprae mucrlo por calor (KML). En el estudio se usaron 3 preparaciones combinadas: (I) 0.1 mg BCG + 6 x 108 KML, (II) 0.1 mg BCG + 5 x 107 KML, y (III) 0.1 mg BCG + 5 x 106 KML; junto con (IV) 0.1 mg de BCG solo, y (V) solución salina. Cada individuo recibió, al azar, una de las 5 preparaciones mencionadas. Tanto al inicio como a las 12 semanas después de la vacunación, los individuos también fueron probados con el antigeno soluble de M. leprae de Rees (MLSA) y con lepromina A. Las reacciones al MLSA se midieron a las 48 horas; aquellas a la lepromina A, a las 48 horas y a las 3 semanas. El carácter y el tamaño de la respuesta local en el sitio de vacunación se registró a las 3, 8, 12, 15 y 27 semanas. El tamaño promedio de las reacciones hacia el M LSA y hacia la lepromina A en los grupos vacunados fue significativamente mayor que en el grupo control inoculado con solución salina, ésto demostró claramente la capacidad sensibilizante de las vacunas, el cual fue mayor con la vacuna I. No hubieron diferencias significativas entre las vacunas II, III y IV, aunque, generalmente, se observó un efecto de dosis-respuesta. El efecto sensibilizante atribuible a la vacuna se observó más claramente en los niños que en los adultos. Las conclusiones anteriores fueron las mismas independientemente de cuales resultados fueron considerados (reactividad al MLSA o a la lepromina). Un hallazgo importante del estudio fue que, al inicio, las reacciones de Mitsuda proporcionaron una medida del efecto sensibilizante de la vacuna. La curación de las lesiones inducidas por vacunación ocurrió sin contratiempos. En más del 90% de los individuos vacunados, las lesiones habían sanado hacia la semana 12 en los grupos que recibieron las vacunas 11, III, y IV, y hacia la semana 15 en el grupo que recibió la vacuna I. Los resultados mostraron que la vacunación con BCG o la combinación de vacunas fueron igualmente seguras en los individuos con o sin cicatrices previas por BCG. Trece personas, de 10 años o mayores, desarrollaron linfadenitis supurativa hacia la semana 8 (7 en el grupo de la vacuna I, 3 en cada uno de los grupos II y III), sin embargo, la curación fue pronta después del drenado de las lesiones.Reports on vaccines based on Mycobacterium leprae and cultivable mycobacteria have been promising and have raised hopes for the primary prevention of leprosy. Convit, et al. demonstrated probable prophylactic efficacy of a combination vaccine of BCG and killed M. leprae (3). In a recent publication, based on preliminary results during the first 5 years of follow up in the Venezuelan vaccine trial, Convit, et al. observed that there was no evidence that BCG plus M. leprae offered substantially better protection against leprosy than BCG alone (4). In the same study, based on a retrospective case-control analysis as well as prospective data, Convit, et al. found that BCG by itself offered substantial protection against leprosy, which could explain the apparent lack of additional protection by the combination vaccine. In India, in a large BCG prophylaxis trial against tuberculosis and leprosy, it was seen that BCG offered an overall protection of about 24% against leprosy. Hence, seareh for a better vaccine for the prevention of leprosy continues (11).

A comparative leprosy vaccine trial using available candidate vaccines, e.g., ICRC, Mycobacterium w, and BCG plus killed M. leprae, was proposed with a view to find a primary preventive intervention that could be useful in leprosy eradication efforts. The Drugs Controller of India had cleared the ICRC and Mycobacterium w vaccines for large-scale trials. Before considering BCG plus killed M. leprae vaccine for use in a large-scale trial in India, it was felt necessary to examine its acceptability in the Indian population and also its potential use as a prophylactic vaccine in terms of its sensitizing effect. The protocol for this study was ethically cleared and permission from the Drugs Controller of India was obtained to undertake the study. The study was conducted from August 1989 to January 1990 in two villages in the Thiruthani taluk of Chingleput District, Tamil Nadu, India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Vaccines and immunologicals

The following vaccine/control preparations and immunologicals were used in this study:

Vaccine preparations.

I = BCG 0.1 mg + 6 x 108 killed M.leprae (Lot IV) per dose.

II = BCG 0.1 mg + 5 x 107 killed Al.leprae (Lot IV) per dose.

III = BCG 0.1 mg + 5 x 106 killed J11.leprae (Lot IV) per dose.

IV = BCG 0.1 mg (Batch 308, June 1989,viability count of 6.6 x 106 per ml) per dose.

Control preparation.

V = Normal saline (sodium chloride injection, LP. 0.9% w/v).

Immunologicals. 1) Rees' M. leprae soluble skin-test antigen, 1 µg protein/dose (Lot Wel-4-EFl) and 2) lepromin-A, 30-40 million bacilli/ml (Lot J 15-4, 21-7-88).

Freeze-dried BCG vaccine was supplied by the BCG Vaccine Laboratory, Madras, India. Suspensions of vaccine-grade, armadillo-derived, killed M. leprae, in three different concentrations, as well as Rees' M. leprae soluble skin-test antigen (MLSA) and lepromin-A were supplied by the IMMLEP Program of the World Health Organization. The killed M. leprae suspensions were received frozen, and were kept in the same condition until their final use. Normal saline was procured locally.

To obtain the combination vaccines. 2 mg of freeze-dried BCG was reconstituted by adding 2 ml of each of the three doses of killed M. leprae suspension. Similarly, 2 mg of freeze-dried BCG was reconstituted by adding 2 ml of normal saline to obtain the BCG vaccine. Reconstitution was done just before vaccination. Care was taken to avoid direct sunshine while reconstituting the vaccines, as well as at the time of vaccination. The vaccines were kept cool in ice boxes, and were used within 6 hr from the time of reconstitution.

Due to the methods necessary for reconstitution of the vaccines, it was not possible to keep the study completely double blind. However, each of the five "vaccines" were given two different codes and the final preparations were kept in identical-looking, amber-colored ampoules. Thus, at the time of the actual administration of the vaccines, there were similar-looking, amber-colored ampoules having 10 different code numbers. The key to the codes was available only with the statistics section of the unit.

Study population

We recruited 50, 50, and 100 individuals in the age groups 1-6, 7-12, and 13-70 years, respectively, for each of the five different study arms. Leprosy patients and suspected leprosy cases, tuberculosis patients, obviously ill and infirm individuals, pregnant and lactating women were not included in the study. A total of 3560 individuals were enumerated in the two villages and 2379 were examined by paramedical workers for the presence of a BCG scar and for leprosy manifestations. This area is endemic for leprosy and also known to have a high level of nonspecific sensitization (21).

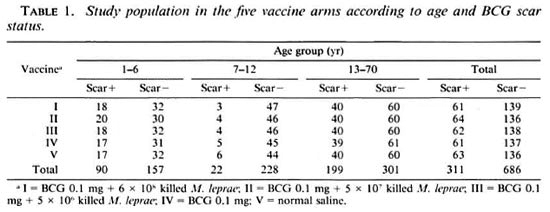

As per the design of the study, attempts were made to include 40% of the study population with BCG scars in each of the three age groups. However, in the age group 7- 12 years, individuals with BCG scars were very few in number and only about 9% with BCG scars could be recruited. Of individuals free from leprosy manifestations and with the desired proportion with BCG scars, 1175 were examined by a medical officer for eligibility. 1033 were found to be fit for vaccination, and 997 were actually recruited for the study. The distribution of the study subjects by age and BCG scar status, separately for the five arms of the trial, is given in Table 1. Recruitment into the study was done by individual randomization from each of the six strata by age group and BCG scar status. Out of the 997 individuals recruited. 49% were males and 51% were females.

Intake and follow-up procedures

Recruitment of the eligible individuals for the study was completed over 15 days. Written consent was obtained from volunteers (parent, in case ofchildren) on a form printed in the vernacular, in the presence of a witness, a responsible person from the village. The study subjects received 0.1 ml of one of the five "vaccine" preparations by random allocation intradermals on the left shoulder at a single site. At the same time, they were tested with 0.1 ml of Rees' MLSA and lepromin-A on the upper third dorsum of the left forearm and midvolar part of the right forearm, respectively. The transverse diameter of indurations, in millimeters, to Rees' MLSA and lepromin-A were measured at 48 hr and, for absentees, at 72 hr. (The reader was kept "blind" about the code of the vaccine received by the study subjects.) These reactions were also graded according to the density of indurations (7). Grade I indurations are the most dense, with raised, sharply demareated, perceptible and palpable borders. Grade IV indurations are the least-dense swellings, not perceptible visually but palpable on light touch. Grades II and III indurations have consistency in between that for Grades I and IV. The size of the lepromin-A late reactions was measured at the end of 3 weeks. The size and character of the local response at the vaccination site were recorded at 3, 8, 12, 15, and 27 weeks. The character of the vaccination lesion was recorded as: nodule (N), pustule (P), ulcer (U), pustule with crust (C), dry crust (D), scar partly covered with crust (Q), or completely healed scar (S).

Twelve weeks after intake all of the individuals were retested with Rees' MLSA and lepromin-A on the mid-dorsal aspect of the right forearm and midvolar aspect of the left forearm, respectively. The postvac- cination reactions to Rees7 MLSA was read at 48 hr and that to lepromin-A at 48 hr and at 3 weeks.

Throughout the period of the study, a medical officer accompanied the field teams. In addition, he visited the villages every week. Individuals reporting any vaccination-related complaints were examined by him, and the findings recorded.

Statistical analysis

The paired t test was used to test for the significance of mean increases in reaction size. The chi-squared test was employed for comparing proportions. A t test (if permissible) or the Mann-Whitney U test was employed to compare two means. For comparing more than two means, the F test (if permissible) or the Kruskal-Wallis test was used.

RESULTS

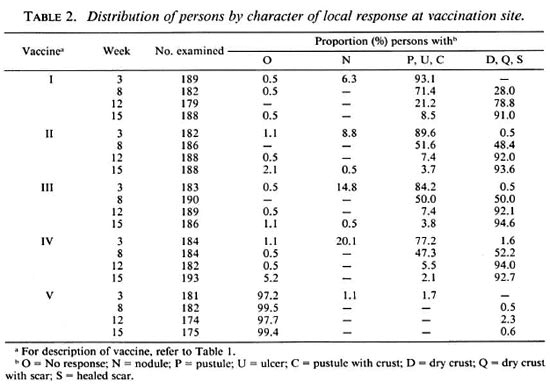

Local response at vaccination site. Information on the character of the local response at the vaccination site for the different vaccine preparations, separately for the three age groups, is given in Table 2. The evolution of local lesions following vaccination with vaccines II, III and IV was similar (p > 0.7). By the eighth week, nearly 50% of these lesions were almost healed (D, Q or S categories). In comparison, lesions following vaccination with vaccine I took a longer time to heal, only 28% of the lesions showing signs of healing by the eighth week (p < 0.01 ). However, by week 1 5 more than 90% of the lesions had healed in all the four vaccine arms. Lesions at the vaccination sites evolved slower in individuals in the age group 1-6 years. In this age group, for vaccines I to IV, 21.7%, 28.3%, 38.3% and 43.2% individuals, respectively, had either no lesion (O) or only a nodule (N) at the third week as compared to 1.1%, 3.3%, 4.5% and 8.5% individuals in the age group 13- 70 years (p < 0.01). The evolution of the vaccination lesions was similar (p > 0.1) in the BCG scar-positive and -negative groups.

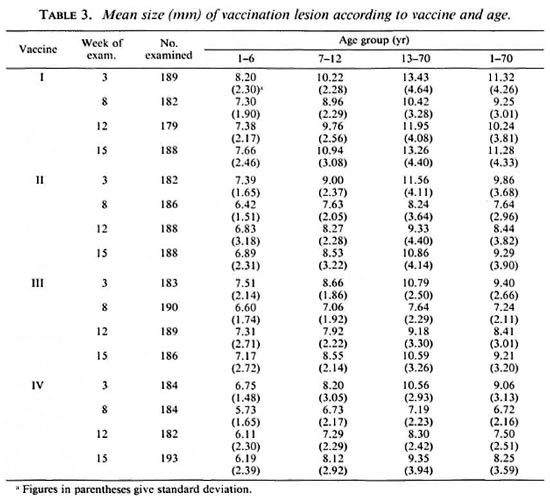

Table 3 gives the mean size of the vaccination lesion at weeks 3 to 15. The mean size of the vaccination lesion increased with age (p < 0.01). In each age group, it was the highest among persons receiving vaccine I (p < 0.01). It was seen that the mean size of the vaccination lesion was associated with the dose of the vaccine. However, for vaccines II, III and IV the differences in the mean sizes of vaccination lesions were small and not statistically significant (p > 0.1). Considering the age group 1-70 years, the mean sizes of vaccination lesions at week 15 were 11.3, 9.3, 9.2, and 8.2 mm for vaccines I, II, III and IV, respectively. The mean sizes of the vaccination lesions in the BCG scar-positive and BCG scar-negative individuals did not differ significantly in any of the vaccine groups (p > 0.05). Local responses at the vaccination sites were again examined at week 27. There were no persistent ulcers in any of the vaccine groups, and the only lesion at week 27 was a completely healed scar. Of the 712 vaccinated individuals examined, 701 (98.5%) exhibited a scar due to vaccination.

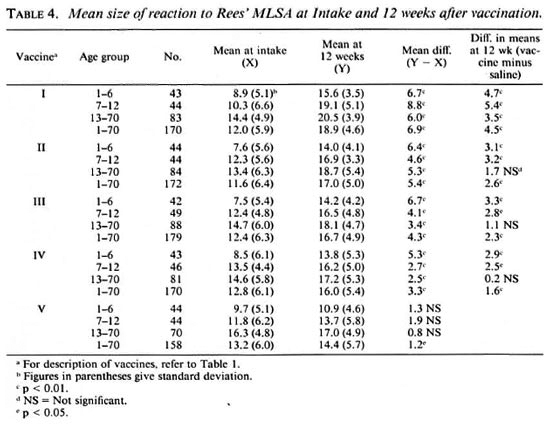

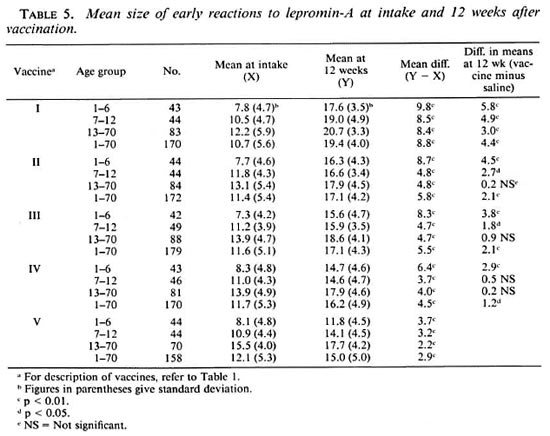

Rees' MLSA and lepromin-A early reactions at intake. The results of testing with Rees' MLSA and lepromin-A are presented in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. The patterns of results for the two tests were similar. The mean sizes ofreactions to both Rees' MLSA and lepromin-A increased with age (p < 0.01). They were generally similar in both BCG scar-positive and -negative groups (p > 0.05). The mean sizes ofreactions to both Rees' MLSA and lepromin-A were similar (p > 0.2) in all the five "vaccine" groups, although a tendency for the mean size to be slightly higher in the normal saline group as compared to that in the groups receiving vaccine was observed.

Considering reactions of 8 mm and above as positive to Rees' MLSA, based on the antimode of the distribution of reactions, 59.1%, 81.8% and 94.3% of the individuals in the normal saline group were positive to the test in the age groups 1-6, 7-12 and 13-70 years, respectively. The distributions of reactions to lepromin-A did not show bimodality. However, considering reactions of 8 mm and above as positive, 50.0%, 79.5% and 98.6% of the individuals in the normal saline group were positive to the test in the age groups 1-6, 7-12 and 13-70 years, respectively.

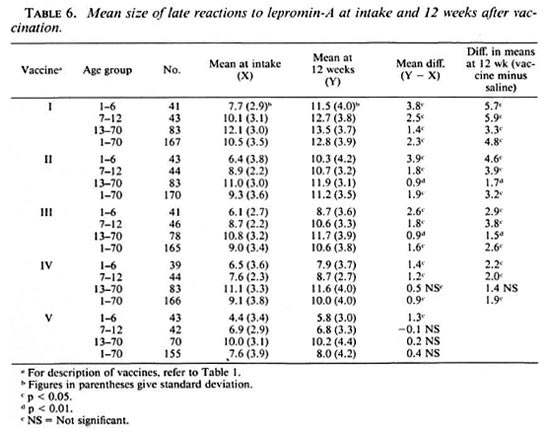

Lepromin-A late reactions at intake. The mean size of late reactions to lepromin-A (Table 6) at intake increased with age (p < 0.01). Generally, individuals with BCG scars had a larger mean reaction size than those without BCG scars, but these differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). The mean size of reactions were the largest in individuals receiving vaccine I when compared with any other vaccine group (p < 0.01). They were similar in individuals receiving vaccines II, III and IV (p > 0.7). In individuals receiving normal saline, the mean size of reactions was significantly smaller when compared with that in any other group (p < 0.01). Considering the conventional definition of taking 2+ and 3+ reactions as strongly positive (2:!), 94.0%, 89.4%, 91.5%, 87.3%, and 74.8% of individuals receiving vaccines I, II, III, IV and V, respectively, were strongly positive. In the normal saline group, 39.5%, 71.4% and 98.6% of the individuals were strongly positive in the age group 1-6, 7-12 and 13-70 years, respectively.

Postvaccination reactions to Rees' MLSA and lepromin-A (early). Tables 4 and 5 provide information on the results of postvaccination testing with Rees' MLSA and lepromin-A, respectively. The patterns of the results for the two tests were very similar. It was seen that the mean size of reaction to the postvaccination test was larger than that to the intake test for all the five vaccine groups. The mean increase in reaction size was statistically significant (p < 0.01) in each of the three age groups, for all of the vaccine groups, except for Rees' MLSA in vaccine group V. Vaccine I produced the maximum increase in mean reaction size.

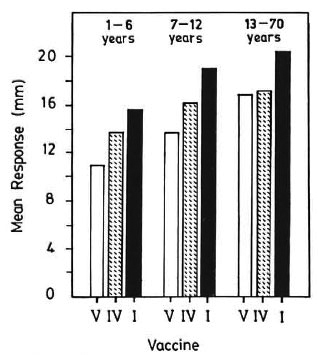

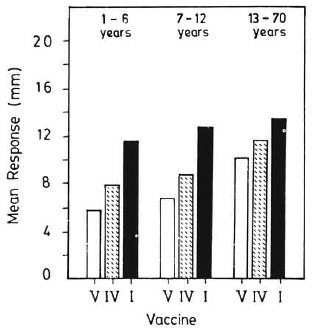

The mean sizes of postvaccination reactions in individuals receiving vaccines ("vaccinated") were compared with mean sizes in those receiving normal saline ("controls"). The mean sizes of postvaccination reactions to both Rees' MLSA and lepromin-A (early) were significantly larger in vaccine group I for all the three age groups, and in vaccine groups II, III and IV for age groups 1-6 and 7-12 years, as compared to those in the normal saline group. The mean postvaccination reaction was the highest in individuals receiving vaccine I (p < 0.01). It was not significantly different in individuals receiving vaccines II, III and IV (p > 0.2) although, generally, a dose effect was seen. The increases in mean postvaccination reactions in the vaccine groups, as compared to those in the normal saline group, were significantly higher (p < 0.01) in age groups 1-6 and 7-12 years than that observed in age group 13-70 years. Mean postvaccination responses with Rees' MLSA and lepromin-A for vaccines I, IV and V are shown graphically in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Fig. 1. Postvaccination response to Rees' MLSA.V = normal saline; IV = BCG; I = BCG + 6 x 108 killed M. leprae.

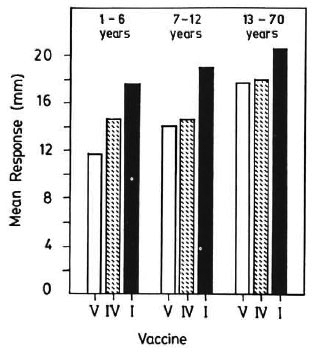

Fig. 2. Postvaccination response to lepromin-A(early). V = normal saline; IV = BCG; I = BCG + 6x 108 killed M. leprae.

Postvaccination reactions to lepromin-A (late). The mean size of postvaccination late reactions to lepromin-A increased with age (p < 0.01). It was significantly higher in the vaccine groups (p < 0.01), but were similar in the normal saline group (p > 0.5). Considering grades I and II as dense, the proportions of densereactions to the postvaccination Rees' MLSA were 34.1%, 16.9%, 13.4%, 8.2% and 3.8% for vaccines I, II, III, IV and V, respectively. These proportions for lepromin-A were 34.1%, 15.1%, 14.5%, 14.1% and 7.6%, respectively.

Postvaccination reactions to lepromin-A (late). The mean size of postvaccination late reactions to lepromin-A increased with age (p < 0.01). It was significantly higher in the vaccine groups as compared to that in the normal saline group (p < 0.01). Among the vaccine groups, it was the highest in vaccine group I (p < 0.01). It was notsignificantly different in vaccine groups II, III and IV (p > 0.05), although a dose effectwas discernible. The mean postvaccination response, attributable to vaccine, was significantly higher (p < 0.01) in age groups 1-6 and 7-12 years as compared to that inage group 13-70 years. Figure 3 shows, graphically, the mean postvaccination responses for vaccines I, IV and V.

Fig. 3. Postvaccination response to lepromin-A(late). V = normal saline; IV = BCG; I = BCG + 6 x108 killed M. leprae.

Among 10, 18, 14, and 21 individuals negative (0, ± or +) to the lepromin-A test at intake, 100.0%, 88.9%, 78.6% and 71.4% became strongly positive (2+ or 3+) to the postvaccination test for vaccines I, II, III and IV, respectively, as compared to 38.5% among 39 individuals in the normal saline group.

Complications to vaccination. Thirteen individuals, 7 following vaccination with vaccine I and 3 each following vaccination with vaccines II and III, developed suppurative regional adenitis. No one in the BCG group or in the normal saline group, who also had lepromin-A test at intake, developed suppurative lymphadenitis. The lymph node enlargement was noticed by the second or third week after vaccination, and fluctuating suppurative adenitis developed around week 8. In 7 cases, the suppurated nodes were incised and drained; in the remaining, they drained off before incision. Healing was prompt after drainage.

Of the 13 individuals, 12 belonged to age group 13-70 years and 1 was a 10-year-old child; 5 of them had previous BCG scars, 8 did not.

DISCUSSION

Convit, et al. reported that a combination vaccine of killed M. leprae with BCG produced a more pronounced and persistent postvaccination sensitization to soluble M. leprae antigens than BCG alone (3). They also demonstrated immunotherapeutic efficacy of the combination vaccine, suggesting its possible utility even among individuals already infected with M. leprae. In our study reported here, three different doses of killed M. leprae in combination with a 0.1 mg dose of BCG were considered along with a 0.1 mg dose of BCG alone and normal saline. In the national program of immunization, BCG is used in a dose of 0.1 mg. Also, in the Chingleput BCG trial, BCG has been shown to offer a limited degree of protection against leprosy, and the level of protection was higher with a 0.1 mg dose than with a 0.01 mg dose (20). Hence, a 0.1 mg dose of BCG in the combination vaccine was considered for the present study. As regards doses of killed M. leprae, the 6 x 108 dose was selected, being the highest dose used in Venezuela (24) and Malawi (9). A 5 x 107 dose was included since this dose was also used in Malawi (9). A 5 x 106 dose is close to the lepromin dose, and was included as the lowest possible dose that could be considered.

In leprosy vaccine trials, clinically diagnosed incidence cases of leprosy, detected in large populations over long periods of follow up, continue to be the only outcome measure. However, in studies designed to assess the immunoprophylactic potential of candidate antileprosy vaccines, one needs to resort to some surrogate measures in spite of their limited applicability. The presence or development of sensitization against M. leprae is generally considered to be a marker for resistance against leprosy (1). However, this is not a fool-proof criterion. In a longitudinal study, it was observed by us that incidence rates for leprosy were similar in both Rees' MLSA-positive and -negative individuals (unpublished data). Dissociation between protection and sensitization with BCG has been demonstrated in studies on tuberculosis (21). The persisting immunological differences between the two vaccine groups measured in terms of Convit's MLSA in the Venezuelan trial did not correlate with the preliminary results on protective efficacy of BCG plus M. leprae and BCG alone (4).

Lepromin conversion (Mitsuda reaction) has been used to measure immunity against leprosy, based on which BCG was considered for prophylaxis against leprosy (8). Convit demonstrated lepromin conversion in leprosy patients and their contacts by using BCG in combination with M. leprae (2). The study by Dharmendra and Chatterjee on the lepromin test reporting susceptibility of lepromin-negative individuals to develop leprosy is often quoted as evidence of the predictive ability of lepromin (6). Walter, et al. demonstrated the utility of the post-lepromin scar as an indicator of resistance against lepromatous leprosy (22).

Lepromin by itself is known to induce sensitization against M. leprae. To overcome this problem, M. leprae-based soluble antigens have been developed to measure sensitization against M. leprae (24). Our earher experience in a highly endemic area for leprosy demonstrated the limitations of the utility of these antigens for epidemiological studies (12). However, these antigens have been found useful for measuring the sensitizing ability of M. leprae-based vaccines in different studies (3, 10, 17, 18).

In the present study, sensitization attributable to vaccination, as measured by Rees' MLSA and lepromin, was considered an indication of a vaccine-induced immune response against M. leprae.

It was seen that in all of the four vaccine groups, in each age group, the mean size of reactions to the postvaccination test was significantly larger than that to the test at intake for both Rees' MLSA and lepromin-A. The difference was the highest in vaccine group I and similar in vaccine groups II, III and IV. However, this difference is the sum total of the effects due to sensitization by vaccine, sensitization by the lepromin test at intake, boosting of existing sensitization by repeat testing, and new sensitization (both specific and nonspecific), and cannot be attributed to vaccination alone. In fact, even in the normal saline group, a small but consistent increase was seen in the mean size of reaction to Rees' MLSA and lepromin at 12 weeks as compared to that at intake. Considering conversion from negativity to positivity to soluble antigens as a measure of the sensitizing capacity of antileprosy vaccines is also problematic and may lead to misleading conclusions due to the effect of regression to mean and other factors mentioned above (5, 14) . Also, as mentioned earlier, the study area is known to have a high prevalence of nonspecific sensitivity, and in the study villages the proportion of positives to skin-test antigens was itself high at intake. In view of the above, for measuring the sensitizing effect of the various vaccines in the present study, the mean sizes of the postvaccination reactions in the vaccine groups were compared with that in the normal saline group.

The mean sizes of postvaccination reactions to both Rees' MLSA and lepromin were significantly higher in the vaccine groups as compared to that in the normal saline group, clearly bringing out the sensitizing effect of the vaccines used in the study. This effect was more pronounced among children than among adults. Since in this population the prevalence of nonspecific sensitivity is high, and by the age of 15 years almost all were positive to the antigens (as observed in the normal saline group) the vaccine effect was masked in the age group 13-70 years. Therefore, in areas with a high prevalence of nonspecific sensitivity, assessment of vaccines in terms of the postvaccination response to antigens is best undertaken in young children. This finding is in conformity with the one reported on postvaccination tuberculin sensitivity for assessing BCG vaccination (16). The sensitizing effect was the highest following vaccination with vaccine I. In vaccine groups II, III and IV, although a doseresponse effect was seen, the differences were not statistically significant. The patterns of results were similar with regard to denseness of postvaccination reactions. A dense reaction would indicate a distinct granuloma. Reactions following vaccination with vaccine I were significantly more dense as compared to those following vaccination with the other preparations. The pattern of postvaccination results was similar for the reactions to Rees' MLSA and for the Fernandez and Mitsuda reactions to lepromin-A. Irrespective of which results one considered, they all led to the same conclusions mentioned above.

It was observed that the simultaneous administration of vaccines marginally suppressed reactions at 48 hr to Rees' MLSA and lepromin-A at intake. The differences were small and statistically not significant. The suppression of tuberculin allergy by simultaneous BCG vaccination has been reported by Narain and Vallishayee (15). In their study also, the depressive effect was so small that they concluded that simultaneous BCG vaccination should not invalidate the results of the tuberculin test.

A noteworthy finding of this study was the observed effect of vaccination on the Mitsuda reactions to the lepromin test at intake. The pattern of these results was similar to that obtained with the postvaccina- tion reactions. The mean sizes of Mitsuda reactions to the lepromin test at intake were significantly higher in the vaccine groups as compared to that in the normal saline group. It was highest in vaccine group I, and was similar in vaccine groups II, III and IV. Thus, the Mitsuda reactions to the lepromin test itself at intake provided a measure of vaccine effect.

There was no apparent influence of BCG scars on reactions to Rees' MLSA or early lepromin-A at intake. This is in agreement with our observations in an earlier study in the same area (12). However, the mean sizes of Mitsuda reactions to lepromin-A at intake were slightly, but consistently, larger in individuals with a BCG scar, although the differences were not statistically significant. Mitsuda reaction positivity following BCG vaccination has been reported in the literature (8). The evolution of local lesions at the vaccination site or mean size of lesions were not significantly different in individuals with and without BCG scars. The occurrence of suppurative adenitis also was not associated with the presence of a BCG scar. In India, BCG immunization is part of the Universal Immunization Programme, and it will not be practical or proper to restrict the antileprosy vaccine trial only to individuals without a previous BCG scar. The results of the present study showed that vaccination with BCG or combination vaccines was equally safe in individuals with and without previous BCG scars.

The vaccination program was well accepted by the community in the study villages. Healing of vaccination lesions was uneventful, except in the 13 persons who developed suppurative lymphadenitis. In more than 90% of the vaccinated individuals, lesions healed by week 12 for vaccines II, III and IV, and by week 15 for vaccine I. In the older age groups, ulcers developed more quickly and the mean sizes of vaccination scars were somewhat larger as compared to those in the youngest age group. Ponnighaus and Fine (l7) have also reported on local ulcers. But the two sets of results are not comparable since in their study, vaccination was given at two different sites by splitting the dose.

Suppurative adenitis following BCG vaccination is a known complication in infants (19). It is supposed to occur due to a deeper vaccination, a large dose of BCG, or a highly potent BCG strain. However, in the present study no case of suppurative adenitis following BCG vaccination was observed in any age group, including the youngest age group. The 13 persons who developed suppurative adenitis were from the groups receiving combination vaccine and, except for one child aged 10 years, belonged to the age group 13-70 years. They all reacted strongly to the intake and postvaccination tests with Rees' MLSA and lepromin. However, most of the individuals in this age group had strong reactions to Rees' MLSA and lepromin, and no particular factor could be identified to predict risk of suppurative adenitis in a given individual. Ponnighaus and Fine have reported metastatic indurations and ulcers in some individuals following vaccination with a high dose of the combination vaccine (17). However, they did not specifically mention suppurative regional adenitis. Convit observed suppurative adenitis in only four individuals in 30,000 vaccinées in the Venezuelan vaccine trial (personal communication). In Venezuela, a lower dose of BCG (0.04 mg) was used in the tuberculin-positive individuals.

In an attempt to reduce the incidence of suppurative adenitis, another study was conducted using a reduced dose of BCG (13). It was possible to bring down the occurrence of suppurative adenitis substantially (only 1 case in 200 vaccinated individuals) without reduction in the sensitizing ability of the vaccine, by using a dose of 0.05 mg BCG with 6 x 108 killed M. leprae.

Acknowledgment. We are grateful to the late Dr. P. N. Neelan, then Director, Central Leprosy Training and Research Institute (CLTRI), Chingleput, India, for permitting us to submit the study protocol to the Ethical Committee of the Institute, which cleared the study. We acknowledge with thanks the support received from the UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Program for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) for the supply of: a) vaccine-grade M. leprae, b) Rees' M. leprae soluble skin-test antigen, and c) lepromin-A used in this study. We thank the volunteers for their willing participation in the study. The hard and meticulous work of the field teams is gratefully acknowledged. The authors wish to thank Mr. N. K. S. Brahaspathy for secretarial assistance.

REFERENCES

1. BLOOM, B. R. Rationales for vaccines against leprosy. Int. J. Lepr. 51(1983)505-509.

2. CONVIT, J., ARANZAZU, N., PINARDI, M. and ULRICH. M. Immunological changes observed in indeterminate and lepromatous leprosy patients and Mitsuda negative contacts after the inoculation of a mixture of Mycobacterium leprae and BCG. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 36(1979)214-220.

3. CONVIT, J., ARANZAZU, N., ULRICH, M., ZUNIGA, M., EUGENIA DE ARAGON, M., ALVARADA, J. and REYES, O. Investigations related to the development of a leprosy vaccine. Int. J. Lepr. 51(1983)531-539.

4. CONVIT, J., SAMPSON, C, ZUNIGA, M., SMITH, P. G., PLATA, J., SILVA, J., MOLINA, J., PINARDI, M. E., BLOOM, B. R. and SALGADO, A. Immunoprophylactic trial with combined Mycobacterium leprae/BCG vaccine against leprosy: preliminary results. Lancet 1(1992)446-450.

5. DAVIS, C. E. The effect of regression to the mean in epidemiological and clinical studies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 104(1976)493-498.

6. DIIARMENDRA and CHATTERJEE, K. R. Prognostic value of lepromin test in contacts of leprosy cases. Lepr. India 27(1955)149-152.

7. EDWARD, L. B., PALMER, C. E. and MAGNUS, K. BCG vaccination. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1953, pp. 33 Monogr. Ser. 12.

8. FERNANDEZ, J. M. M. Estudio comparativo de la reacción de Mitsuda con las reacciones tuberculinicas. Rev. Argent. Dcrmatosif. 23(1939)425-453.

9. FINE, P. E. M. and PONNIGHAUS, J. M. Leprosy in Malawi 2. Background design and prospects of the Karonga Prevention Trial. A leprosy vaccine trial in Northern Malawi. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 82(1988)810-817.

10. GILL, H. K., MUSTAFA, A. S. and GODAL, T. Induction of delayed type hypersensitivity in human volunteers immunized with a candidate leprosy vaccine consisting of killed Mycobacterium leprae. Bull. WHO 64(1986)121-126.

11. GUPTE, M. D. Vaccines against leprosy. Indian J. Lepr. 63(1991)342-349.

12. GUPTE, M. D., ANANTHARAMAN, D. S., NA-GARAJU, B., KANNAN, S. and VALLISHAYEE, R. S. Experiences with Mycobacterium leprae soluble antigens in a leprosy endemic population. Lepr. Rev. 61(1990)132-144.

13. GUPTE, M. D., VALLISHAYEE, R. S.. ANANTHARAMAN, D. S. and DE BRITTO. R. L. J. Extended sensitization study for the candidate antilcprosy vaccine BCG in combination with Mycobacterium leprae. (Paper presented at the XVII Biennial Conference of the Indian Association of Leprologists held at Bhilai, 2-5 January, 1992.) (Abstract) Indian J. Lepr. 64(1992)271.

14. GUPTE, M. D., VALLISHAYEE, R. S., ANANTHARAMAN, D. S. and KANNAN, S. Effect of skin test with M. leprae soluble antigen on reaction to a subsequent test with the same antigen. Int. J. Lepr. 60 (1992) 54-60.

15. NARAIN, R. and VALLISHAYEE, R. S. Suppression of tuberculin allergy by simultaneous BCG vaccination. Indian J. Med. Res. 69(1969)1-5.

16. NARAIN, R., VALLISHAYEE. R. S. and MAYURNATH, S. Post-vaccination tuberculin sensitivity for assessing BCG vaccination in areas with high prevalence of non-specific sensitivity. Tubercle 62(1981)231-239.

17. PONNIGHAUS, J. M. and FINE, P. E. M. Sensitization studies with potential leprosy vaccine preparations in Northern Malawi. Int. J. Lepr. 54(1986)25-37.

18. SMELT, A. H. M., REES, R. J. W. and LIEW, F. Y. Induction of delayed type hypersensitivity to Mycobacterium leprae in healthy individuals. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 44(1981)501-506.

19. TEN DAM, H. G., TOMAN, K., HITZE, K. L. and GULD, J. Present knowledge of immunization against tuberculosis. Bull. WHO 54(1976)255-269.

20. TRIPATHY, S. P. A case for BCG. Ann. Natl. Acad. Med. Sci. (India) 19(1983)12-21.

21. TUBERCULOSIS PREVENTION TRIAL, MADRAS. Trial of BCG vaccines in south India for tuberculosis prevention. Indian J. Med. Res. 72Suppl.(1980)1-74.

22. WALTER, J., TAMONDONG, C. T., GARHAJOSA, P. G., BECHELLI, L. M., SANSARRICQ, H., LWIN, K. and GYI, M. M. Note on some observations about post-lcpromin scar. Lepr. Rev. 48(1977)169-174.

23. WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION. A guide to leprosy control. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1988, p. 29.

24. WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION. Vaccination trials against leprosy. A meeting of the epidemiology sub-group of the Scientific Working Group on the immunology of leprosy. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1985. TDR/IMMLEP/EPD/85.3.

1. M.D., D.P.H.; Central JALMA Institute for Leprosy Field Unit (Indian Council of Medical Research), 271 Nehru Bazaar, Avadi. Madras 600 054. India.

2. M.A.; Central JALMA Institute for Leprosy Field Unit (Indian Council of Medical Research), 271 Nehru Bazaar, Avadi. Madras 600 054. India.

3. M.B.B.S.; Central JALMA Institute for Leprosy Field Unit (Indian Council of Medical Research), 271 Nehru Bazaar, Avadi. Madras 600 054. India.

4. M.Sc; Central JALMA Institute for Leprosy Field Unit (Indian Council of Medical Research), 271 Nehru Bazaar, Avadi. Madras 600 054. India.

5. M.B.B.S., D.P.H.; Central JALMA Institute for Leprosy Field Unit (Indian Council of Medical Research), 271 Nehru Bazaar, Avadi. Madras 600 054. India.

6. M.Sc., Central JALMA Institute for Leprosy Field Unit (Indian Council of Medical Research), 271 Nehru Bazaar, Avadi. Madras 600 054. India.

7. Ph.D., Central JALMA Institute for Leprosy, Taj Ganj, Agra 282 001, India.

Received for publication on 13 February- 1992.

Accepted for publication in revised form on 15 June 1992.