- Volume 57 , Number 2

- Page: 540–51

Operational aspects of multidrug therapy*

Since the Leprosy Study Group of the World Health Organization (WHO) made its recommendation in 1982, 1 in many leprosy control programs multidrug therapy (MDT) has been implemented. 2-4 The concept of and the need for the use of combined chemotherapy for leprosy has been widely accepted.

During this Congress several papers will be presented about the results of MDT. I hope that today we will discuss not only the successes but also the problems which are faced with MDT, especially under field conditions. In my presentation I do not aim at being complete. I will concentrate on those aspects which, in my opinion, are of much importance for the planning and implementation of MDT and for its success.

Multidrug regimens

In many programs the regimens which have been recommended by the WHO Study Group have been introduced.2-6 In some countries, these regimens were modified and especially an initial phase of daily rifampin for multibacillary (MB) patients was introduced.2-5 It has not been shown whether this increases therapeutic efficacy.4-7 In a few countries treatment regimens which include a thioamide, especially in the combination preparation which is known as "Isoprodian," were implemented. 2,6,8-10 There is quite some concern about liver toxicity in patients who are given a thioamide and rifampin simultaneously. Liver toxicity is reported as ranging from 0% to over 20%. 2,8,10-16 Another disadvantage of regimens which include a thioamide is that they are substantially mote expensive than those recommended by the WHO Study Group.17 A disadvantage of the WHO regimen for MB patients is the discoloration of the skin. 2-4,6 In some communities this is not acceptable. 18 In this presentation I will mainly focus on the operational aspects of the regimens recommended by the WHO Study Group.

Pace of MDT implementation

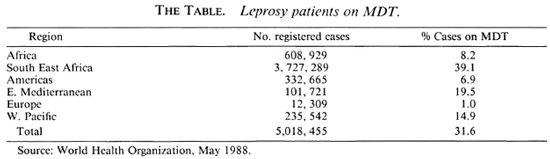

The pace of implementation of MDT is reported as being slow. 3 By early 1988 almost 1.6 million patients, 31.6% ofjust over 5 million registered patients, were on MDT. 19 The Table (p. 551) shows that in the South East Asian region, which has the highest number of registered patients, 39.1% of the patients were on MDT. This is the highest percentage of all six regions. In the African region, with the second highest number of registered leprosy patients, only 8.2% of the patients were on MDT. So far most of the progress has been made in nonintegrated and partially integrated leprosy control programs.

Advantages of MDT

Because of the threat of a further increase in the prevalence of dapsone resistance, there is an urgent need for implementation of MDT in all leprosy-endemic countries.1-3 A great advantage of MDT, particularly for the field situation, is the limited duration of treatment. In the days when dapsone was the only drug available for routine treatment, we faced the problem of premature cessation of treatment by a substantial proportion of the patients. Other advantages of MDT are that the regimens have proven to be effective and well tolerated. 2-4,7,20,21 The threat posed by dapsone resistance and the several advantages of MDT should motivate and challenge managers of leprosy control programs where MDT has not yet been introduced to plan for and execute MDT as fast as possible.

Constraints

The slow pace of MDT implementation indicates that there are obstacles which delay or hamper this process. Obstacles often mentioned include: a) lack of political commitment toward leprosy control in general and MDT in particular; 3,4 b) inadequate health services infrastructure; 3-5,22 and c) shortage of resources. 3,4,22,23

It needs no further elaboration that without political commitment it will be very difficult, if at all possible, to introduce MDT on a large scale. I find it very difficult to define a level of health services infrastructure which is adequate for the implementation of MDT. A WHO Expert Committee on Tuberculosis made a rather challenging statement in 1974: 24 "An effective national tuberculosis programme can be delivered under any situation, provided planning and application are guided by a clear understanding of the epidemiological, technical, operational, economical and social aspects." I should like to propose that this is also adopted for leprosy control.

The experience that implementation of MDT appears to be operationally feasible under very difficult field situations, such as those in Nepal, is very encouraging. 25-27 Additional resources are needed, especially during the first years of implementation of MDT. The higher cost for drugs is obvious, and field operations often become more expensive, in particular the costs for transport and daily allowances. In some programs, additional staff have to be employed, and training and re-training of staff require additional financial input. Provided a realistic plan of operations was prepared, most programs have been able to mobilize additional external resources.34 In my opinion, a shortage of resources should not be an insuperable contraint for the implementation of MDT.

Requirements for MDT implementation

Even if there is a commitment to MDT and the health services infrastructure is adequate, there are other requirements which should be fulfilled before MDT can and should be implemented. The most important requirements are: a) Plan of operations-this should describe the phasing of the program, targets, requirements, managerial aspects, monitoring and evaluation. b) Manual for MDT implementation -In the manual all technical and operational aspects of MDT should be given in detail. 28-32 c) Job descriptions of all cadres of staff involved in the MDT program; d) Training and re-training of staff, c) Financial resources, in particular for drugs, or a guaranteed supply of the drugs, f) Provisions for uninterrupted delivery of the treatment to the patients, g) Transport facilities for supervisory staff, h) Provisions for regular supervision and support of peripheral staff and supervisors.

After these requirements have been fulfilled, the foundation for implementation of MDT has been laid. I am convinced that MDT cannot be implemented successfully without this foundation. Ifessential requirements cannot be fulfilled, MDT should not be introduced.

Ensuring proper planning and implementation of MDT is a managerial task par excellence. Implementation of MDT requires experts who have not only a clear understanding of the technical and clinical aspects of leprosy control, but also the managerial capacities to cope with all of the important operational aspects. One reason which may delay MDT implementation is the absence of this kind of expertise. This could, particularly for the process of planning of MDT, be solved by providing external experts.

Revision of leprosy control services

In order to be successful with the implementation of MDT, most components of the leprosy control services need to be reorganized or upgraded. For other aspects new policies have to be defined, including: classification of patients, skin smear services, monitoring, duration of MDT, surveillance after MDT, diagnosis of relapses, training, and supervisory activities.

Classification of patients. Because of the different treatment regimens for paucibacillary (PB) and multibacillary (MB) patients, we have to classify each patient into one of these two categories before starting MDT. The criteria for classification has been defined by WHO 33 and are used in many leprosy control programs.

The present strategy relics heavily on the results of skin-smear examinations. However, in many centers in leprosy-endemic countries the standards in taking, handling reading, and recording of skin smears are often insufficient or poor. 13,34,35 It may be feared that part of the patients are wrongly classified as PB and receive insufficient treatment. 2-4,35 This is not only a risk for the individual patient, it may also jeopardize the reputation of MDT. The recent recommendation 36 to consider patients with a bacterial index (BI) of 1 as MB also, for the purpose of allocation of the MDT regimen, leaves the problem of the low standards of skin-smear services unsolved.

The question arises whether for classification purposes we should continue to rely heavily on the results of skin-smear examinations. It may be considered to give more weight to clinical symptoms or even to classify patients routinely on clinical grounds only. Skin smears should then be examined in cases of doubt.

In programs which use the Madrid classification, borderline patients have to be reclassified either PB or MB. Past records are not always complete and reliable, and in many programs skin-smear examination was not routinely done. In cases of uncertainty about the original classification, classification as BL gives patients the benefit of the doubt.

Skin-smear services. The results of skin-smear examination are not only used for classification of patients, but also for several other decisions in leprosy: a) assessment of effect of treatment during MDT, b) duration of MDT in MB patients, and c) diagnosis of relapses.

Recently Georgiev and McDougall expressed their concern about the unsatisfactory state of affairs of skin-smear techniques.3 5 They conclude that, despite several efforts by international ageneies and national programs who prepared manuals and guidelines and conducted many seminars and workshops, the situation is unacceptable by any standard and unlikely to change. They propose that the present approach should be radically revised as a matter of urgency. Their recommendations, which in my opinion should be given very serious consideration, are: a) to close virtually all one-man peripheral laboratories for skinsmear examinations and to develop simultaneously a central referral laboratory, and b) to couple this change with a fundamental reconsideration of the value of skin-smear examinations for crucial decisions in leprosy.

Monitoring. Monitoring relates to the following activities:

Monitoring of clinical progress and drug intake. In order to assess clinical response to treatment and to detect possible reactions and adverse effects of the drugs, patients have to be examined periodically. For decision making, the examination of skin smears during the first 2 years of MDT is irrelevant. It puts, especially during the initial phase of implementation of MDT, a heavy burden on the laboratory services.

If MDT is continued until skin-smear negativity, one can expect that a patient needs at least as many years of MDT as the BI value at the start of the treatment. This is based on the experience that with MDT the decline in BI is not faster than with dapsone monotherapy and in the order of 0.5 to 1 point on the logarithmic scale per year. 2,4,37,38 A patient with a starting BI of 5 is likely to need effective chemotherapy for at least 5 years; hence the result of skin-smear examination may only be required 5 years after starting MDT. For reasons mentioned earlier, I should like to make a strong plea for limiting routine skin-smear examinations as much as possible.

In order to detect reactions which involve the nerves, regular assessment of nerve functions is of great importance. 39 Preferably this should be done every month. Voluntary muscle testing (VMT) and sensation testing (ST) and a well-defined policy for antircaction treatment should be part and parcel of an effective MDT program. 39 Thus regular VMT and ST are very important, but skin-smear examination during MDT is not.

Monitoring the drug intake of the unsupervised component of MDT can easily be done periodically with the urine spot test.40 The test is very simple and can, in our experience, easily be applied under routine field conditions.41 We tested over 11, 500 urines in the field during several treatment rounds. Over 80% were positive for the presence of dapsone.42 The results after introduction of MDT were significantly better than those prior to MDT. In most programs it may not be feasible to do home visits for pill counts. Sometimes it may suffice to just count the pills patients still have when attending the next treatment session.

Operational assessment. Indicators for monitoring and evaluation were recommended by WHO in 1985. 43 I should like to pay attention to some indicators which are recommended for monitoring MDT: a) the proportion of MB patients on regular MDT during the year, and b) the proportion completing MDT among PB patients expected to complete. (The second indicator refers to patients who started MDT during the first 3 months of the year only.)

Since MDT, in the case of MB patients, has to be taken for a relatively long period, monitoring of the regularity of attendance is certainly of importance. However, what we really want to know is what proportion of patients out of those under MDT did complete the course of MDT according to instructions. For monitoring the results of MDT completion, we have introduced cohort analysis. 28

Six-month cohorts of patients are evaluated at the time all patients of that cohort should have had the opportunity of completing MDT. In this analysis, the patients are divided into three groups: a) patients who successfully completed MDT, b) patients who discontinued MDT or had their treatment discontinued due to irregularity of attendance, and c) patients who continued MDT (MB patients with positive skin smears).

Cohort analysis is widely used in tuberculosis control for monitoring completion of chemotherapy. In my opinion and experience, this method is also of much value for monitoring completion of MDT. Through cohort analysis different cohorts of the same area and the same cohorts of different areas can easily be compared. I recommend this type of monitoring. The regularity of attendance has little, if any, value for PB patients. Unfortunately, this information is requested, e.g., by the sponsoring organizations coordinated in ILEP. 44

Duration of MDT. The duration of MDT is defined in terms of the number of required doses of the drugs and the period of time the patients are allowed to complete that number of doses. The usual policy is that PB patients should complete 6 months of MDT within a period of 9 months and MB patients, 24 months of MDT within a period of 3 years.43 However, the definition of duration of MDT in terms of number of doses taken during a certain period of time, regardless of other aspects such as clinical findings, causes several problems.

Let us first consider the consequence of the duration of MDT for PB patients. A proportion of these patients still show clinical activity after six doses of the drugs. This proportion is reported as from 5% to 75%. 4,18,45 The presence of clinical activity is prompting an increasing number of medical officers in charge of leprosy control programs to continue treatment after the six doses of MDT. 3,4,46

Sometimes patients are reclassified as MB and treated with 2 years of MDT for MB patients if signs of clinical activity persist after 12 months. 46 Apparently, it is assumed that persisting clinical activity is due to inadequate chemotherapy and, hence, continuation of chemotherapy is required.

However, available data show that clinical activity resolves in the majority of the patients within 1 to 2 years of stopping MDT. 3,4,26 Unfortunately, the data are not expressed in percentages of patients.

Several leprologists have expressed their concerns about the duration of MDT for PB patients. It has even been proposed to abandon the subdivisions PB and MB and to treat all patients with the regimen for MB patients for a minimum period of 2 years. 47 Such a drastic change of policy would, I think, have to be considered only: a) if it became evident that the 6-month regimen is not sufficient to cure the vast majority of PB patients; b) in programs where an unacceptable number of patients are classified wrongly as PB and hence receive insufficient chemotherapy, when there is reason to expect that the quality of classification methods is not likely to improve within a short period of time; and c) if such a policy would substantially simplify field operations and facilitate the implementation of MDT.

Giving 2 years of MDT to all patients has several consequences, opcration-wisc and financially. The expenditure for the drugs, for example, will be three to four times higher. While there seems to be no evidence of high relapse rates after 6 months of MDT, 3,4 there is a particular problem in PB patients which should be given due attention-development of reversal reactions in BT patients after stopping MDT.

About half of the reversal reactions which we diagnose in BT patients developed after release from MDT. 48 We experienced that several patients did not present themselves promptly in case of a reversal reaction and only attended our services at the time the nerve damage had become already irreversible. This observation has urged us to consider means of continuing the monthly contact with BT patients after their 6 months of MDT. Should we for that reason continue antileprosy treatment, or only give a placebo?

Let us now consider the duration of MDT for multibacillary patients. The recommended period of MDT is minimally 2 years and preferably until skin-smear negativity. 1 Continuation of MDT until skin-smear negativity is more based on tradition 49 from the dapsone era than on scientific grounds. A controversy in regard to continuation of MDT until skin-smear negativity is the suggested relationship between BI results and cure. However, removing of dead bacilli is not a function of chemotherapy, but that of macrophages. 50 Since the decline in BI is not faster with MDT as compared with dapsone monotherapy, a proportion of the patients need MDT for periods up to 5 years. Some patients will need MDT for periods substantially longer than that. In our program about 40% of the MB patients who only received MDT still have positive skin smears after 2 to 3 years of MDT. After 5 years of MDT, 15% of the MB patients are still skin-smear positive. 42

Is it really preferable to continue MDT after 2 years and, if so, what are the benefits? A possible benefit may be the prevention of some relapses, but this we just do not know at present. I think that several of us, especially those who work in clinical leprosy, are too much concerned about relapses. On theoretical grounds, 2 years of MDT is sufficient to cure the vast majority of patients. 38 This is supported by the observation that very few relapses have so far been diagnosed.

For the field situation, continuation of MDT after 2 years has certainly several disadvantages: a) increasing irregularity of attendance. We have experienced that patients who have been under MDT for over 3 years tend to come less regularly for their treatment, b) prolonged risk of toxic side effects of the drugs; c) such an open-ended treatment period will promote among patients, staff, communities and policy makers the belief that leprosy is still incurable, d) the increased expense of the drugs. We calculated that, in our program, continuation of MDT until skin-smear negativity would, for patients who receive MDT only, increase the expenditure on antileprosy drugs at least 75%.

So, 1 come back to my question: Is it really preferable to continue MDT until skin-smear negativity?

If one weighs the possible benefit, which has not been proven, against the several disadvantages, especially in operational field terms, I am inclined to conclude that with the present experience with MDT we have no convincing reasons to maintain the recommendation for continuation of treatment until skin-smear negativity.

I agree with the THELEP Steering Committee that there is an urgent need for trials with MDT regimens of fixed duration. ALERT has started one such study in our so-called "AMFES" project. The purpose of such studies is to establish the shortest duration of MDT which would still not cause more than an acceptably low proportion of relapses.

Surveillance after MDT. WHO has given the following recommendations for surveillance after completion of MDT: 43 a) for PB patients, clinical examination at least once per year for a period of 2 years; and b) for MB patients, clinical and bacteriological examinations at least once per year for a minimum period of 5 years. The two main questions regarding these recommendations are : Are they feasible? Are they sufficient?

Are they feasible? It is beyond the possibilities of most leprosy control programs to carry out active surveillance. In most programs one has to rely on voluntary reporting by patients. This should be reinforced by health education. Early diagnosis of relapses and reactions depends, to a large extent, on the awareness and knowledge of the patient and the medical staff concerning suggestive symptoms, and the motivation of the patient to consult the medical services. In our program much attention is given to the education of the patients at the time of release from MDT. Patients are given a "Release from Treatment" card with date of first follow-up examination. Notwithstanding this, so far only about 40% of the patients attended one or more times for follow-up examination. 48

I think that in most leprosy control programs it is not feasible to ensure surveillance of patients of regular frequency and for a duration of several years. However, since most patients initially reported themselves with symptoms of 'leprosy, we may assume that they will also do so in case of the reappearance of the disease.

Studies about relapse rates should be done by some well-organized leprosy control programs, preferably under different operational circumstances. Other programs may follow the policy which is commonly used in tuberculosis control: instruct patients to report for examination as soon as symptoms recur.

Are they sufficient? Some leprologists advise waiting at least 3 or even 4 years after stopping MDT before evaluating the success of MDT in PB patients.5 1 A follow-up period of only 2 years would then certainly be too short for detection of relapses in PB patients. Previously, I mentioned the risk BT patients have in regard to the development of a reversal reaction after stopping MDT. In order to diagnose and treat a reaction as early as possible after its occurrence, BT patients who received 6 months of MDT only should be examined more frequently than only once per year, especially during the first 1 to 2 years after release from MDT, at which time they are most at risk of developing a reversal reaction. I strongly recommend examination of these patients at 3-month intervals.

Diagnosis of relapses. When talking about relapses, I refer to the reappearance of disease in patients who, in the past, successfully completed an adequate course of antileprosy treatment. 39 So far only very few relapses have been reported after MDT. 3,4,13 general opinion is that conclusions about relapse rates should be made with caution.

The follow-up periods after cessation of MDT are generally considered to be too short, especially for MB patients. 3,13,52 Acceptable relapse rates have not been defined. Relapse rates are predicted as less than 5%,5 3 from 1% to 2%,2 2 not more than 1%,4 or less than 1%.4 Cure rates of 90% or higher5 2 are considered acceptable.

There are several uncertainties and problems related to the diagnosis of relapse: a) Paucibacillary patients: In many BT patients it appears to be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish, both on clinical and histopathological grounds, a relapse from a late reversal reaction. 2-4,13,48,54,55 Since the clinical symptoms in both conditions are due to similar immune responses to mycobacterial antigens, the available techniques cannot give a conclusive answer. I should like to stress that, in routine services, the appropriate treatment of a reversal reaction which involves the nerves should be given the highest priority. The diagnosis and treatment of a possible relapse is less of an emergeney and should be considered only after insufficient response to corticosteroids, b) Multibacillary patients: The reappearance of morphologically intact bacilli in smears is considered important proof for relapse. 4,13 However, the examination of the morphological index has several practical problems, including the accuracy and reliability of the results. 37,38,56 The choice of appropriate sites for taking the skin smears is another practical problem.

Growth of the bacilli in the mouse foot pad cannot be applied routinely, and even in cases where mouse foot pad facilities are available, the decision for retrcatment often has to be taken before the results of mouse foot pad inoculations have become available.

In most leprosy control programs we have to rely on the appearance of new skin lesions, preferably supported by an increase in the BI. Relapses suspected by field staff should be confirmed in a referral center. Although skin-smear positivity can precede the appearance of new lesions, I do not like to support a policy of doing frequent routine skin-smear examinations in the absence of new skin lesions.

The finding of a BI of 1 or 2, without suspect symptoms or signs, in a patient who has been released from MDT with negative skin smears is, certainly in the field situation, very confusing. Such findings may very well be due to chance. There is certainly a need for standard criteria for the diagnosis of relapses. The examination of skin smears has several limitations and problems. Early new lesions can easily be missed by staff with limited experience in leprosy. If a simple tool can be made available, such as a urine dipstick, sensitive and specific enough to reliably indicate the rise in levels of Mycobacterium leprae antigens, this could be ofgreat help in the detection of MB relapses.

Training. Next to the chemotherapeutic regimens, people are the most important component of the implementation of MDT. Training of all staff involved in the program is of extreme importance. The performance of the field staff has to make things work. Training should be task oriented, while major attention should be given to those aspects which are critical for the proper execution of tasks. A main weakness in training is that most attention is given to clinical aspects rather than to managerial skills. Fortunately, training in managerial skills for supervisory staff and managers of leprosy control has recently started to be implemented. 57 Experience with this kind of training is being acquired now. Training should be a continuous process. We experienced that conducting training in phases is very effective. Prior to each phase of MDT implementation, training of field staff concentrates on the essential activities which have to be carried out during that particular phase.

Supervisory activities, provision of supervised treatment. Supervisory activities are related to all aspects of MDT. These should be fully considered at the time leprosy control activities are being reorganized for the implementation of MDT. The crucial condition for success of MDT is the proper delivery of the supervised treatment. If supervised treatment cannot be secured without interruption, even the most efficacious regimens will give unsatisfactory results. Places and dates of treatment delivery should be clearly defined and should be as convenient as possible for the patient. In our program, clinics are conducted during market days when the rural patients, widely dispersed, usually come to the village or town anyway.

Especially during the initial phase of MDT implementation, the responsibility for the delivery of MDT should be given to a limited number of medical staff only. Supervisors, especially trained paramcdicals who are mobile and responsible for an area they can cover in a 4-week cycle, may, in many programs, be the most appropriate staff to have this responsibility. MDT is given partly supervised to ensure optimal drug intake and to prevent unauthorized use of drugs, especially rifampin.

At the time the number of patients under MDT has decreased substantially arid experience has been gained with the many operational aspects of MDT, the involvement of the general medical staff in the delivery of the drugs should be considered. Regular supervision, e.g., once every 3 months, remains very essential. The introduction of registration and accounting systems for the drugs and regular checks, especially on the use of rifampin, are essential.

It is absolutely necessary to secure budgetary provisions or a guarantee for obtaining the drugs before undertaking MDT in an area. Provisions should be secured for a period of at least 2 years and preferably longer. A practical problem related to this is that several sponsoring organizations guarantee support for only a period of 1 year at a time.

Another aspect which requires attention is securing continuation of M DT during periods when patients cannot reach the clinic, e.g., during rainy seasons. This problem can be solved by providing the patients, for such periods, with blister packs of the drugs. 58

Situation after MDT implementation

Some years after successful implementation of MDT, the number of patients under chemotherapy will have decreased to quite an extent. 5,10,59,60 In our program a reduction of up to 25% of the initial number of patients under antileprosy treatment was achieved within a period of 6 years. 42

The practical situation will be that, with increasing coverage of MDT, the number of patients needing life-long care due to disabilities will gradually outnumber the number of patients under chemotherapy. We estimated that in our control area about 3000 patients will be under chemotherapy from 1991 onward, compared to over 21,000 patients in early 1983. In the 1990s, the number of patients with a disability grade of 1, 2, or 3 will be at least 8000. This clearly shows that patients under MDT represent only part of the workload.

There is concern that the very success of control could lead to a decline in interest in the disease.6 1 Since MDT requires much effort and additional work, it may be logical to wait with the strengthening of activities toward disability prevention until the time the majority of the patients have been released from MDT.5 5 However, the planning and organizing of such activities should already start before the final phase of MDT implementation has been reached. Continuing patient care not only helps the individual, it also reinforces the credibility of MDT. 3,23

It is outside the scope of this presentation to discuss the organization of patient care. However, I should like to say a few words. Care should as much as possible be organized in consultation with the patients and in the communities. A very important priority is the prevention of disability in patients who have loss of sensation in their limbs. 62 This is one of the major problems in leprosy; 18% of our patients have loss of protective sensation of one or two foot soles at the time of diagnosis. 63 The techniques and means for the prevention of deformity and disability are available. Whether these are effective under several conditions is an important aspect for further study.

Another matter which has been stressed for several years is the integration of leprosy control within the general health services and, as much as possible, through the primary health care approach. 2-5,64,65 There are several limitations of vertical programs. 3,64,65 There are also constraints which hinder the integration. 64,66 Integration does not imply that all specialized staff and services should disappear. 3,64,65 It means that leprosy control activities will become the responsibility of the permanent multipurpose health services. 64,65 Especially for technical supervision, advice and referral, specialized staff and services will continue to be needed. The existence of an adequately functioning health care service is a prerequisite for integration. 65 In some instances, the leprosy control infrastructure may be used for strengthening the general health services.

Final remarks

In the previous parts of my presentation, I have discussed that with MDT several operational and technical aspects of leprosy control have become more complex and critical. If we want to appraise the potency of MDT to cure the leprosy patients, we have to consider two aspects: a) When applied optimally, it is likely that MDT can cure over 90% of the patients. This is based on theoretical grounds and on the preliminary results of several studies, b) What will be the expected results when MDT cannot be implemented or is not implemented optimally? To show that these aspects can be dramatically different, I should like to draw a parallel with the result of chemotherapy in tuberculosis.

With the so-called "standard regimen" over 90% of tuberculosis patients can be cured when maximum compliance with clinic attendance and drug intake is secured. 67 However, when applied under routine field conditions, in many developing countries cure rates of only 30% to 45% were achieved. 67,68 In other words, instead of a success, an outright failure. The most important reasons for unsatisfactory results of chemotherapy in tuberculosis are irregularity of drug intake and premature termination of treatment, mainly by self-discharge. 69

Certainly, with dapsone monotherapy patient default and irregularity of drug intake were and still are serious problems.70-72 New treatment regimens alone will not solve these problems. Although an increase in regularity of attendance and compliance with drug intake had been reported since introduction of MDT, 3-5,20,25,45,55 we still face these problems. Irregularity of intake of dapsone and clofazimine poses the threat of relapse with rifampin-resistant M. leprae. 73 It is not known under which conditions drug resistance may occur.

There are two important questions in this respect: a) What is the critical level of drug intake for the supervised as well as the unsupervised components of MDT? A WHO Study Group had defined regular treatment as the receipt of two thirds of the recommended doses of MDT during a period of usually 1 year. 43 In the field situation, this relates to the intake of the supervised doses of the drugs and the collection of the other drugs for self-administration at home. The rationale for two thirds is based on the assumption that adequate MDT implies receiving 24 doses of MDT within 36 months. I could not find a scientific background for this assumption, b) Is there a period during the course of MDT in which regular drug intake is most critical?

Apart from the risk of drug resistance, another most important question is: c) What proportion of patients should successfully complete MDT in order to have an impact on the transmission of the disease?

As I have indicated, there could be a great discrepancy between cure rates which can be achieved under optimal conditions and cure rates which are achieved under routine field conditions. In view of the questions about drug resistance and minimal cure rates which should be attained, I think there should be clear definitions about the minimum results which should be achieved with MDT, e.g., at least 75% of the patients should successfully complete MDT. If this requirement cannot be met, MDT should not be introduced or extended in a program.

The tools for curing patients and preventing and overcoming drug resistance are available. If we consider operational aspects, we have to consider how these tools should be and, in actual practice, are used. There is a definite need for operational studies which aim for better implementation of leprosy control in general and MDT in particular. What I have in mind are studies which aim at gaining knowledge and developing methods which can be applied in other programs.

When asked to define subjects for operational studies in MDT, I would recommend: a) reasons for noncompliance: In most studies in leprosy control, patient-related factors are considered. 70-74 Studies in tuberculosis control show that reasons for patient default are often to be found in the services which are rendered. These are , for example, negative attitudes of the staff, interruptions of drug supplies, insufficient instructions to patients, and inconvenient consultation hours. 69 b) methods to improve the shortcomings of the services.

I should like to say a few words about the chemotherapy itself. In order to aid compliance, a combination preparation of dapsone and clofazimine should be made available. There is a need for new MDT regimens. Developments in this field look very promising.4,75 Also, the use of already existing drugs may be explored. In a recent publication, a possible effect of pyrazinamidc in killing persistent M. leprae is indicated. 76 New drug combinations should not only be effective, safe and acceptable, they should preferably also have the following characteristics: require little or no supervision, patient compliance should be less critical than for the present regimens, and they should cure the patients within a period of less than 2 years.

Finally, with an estimated number of over 5 million patients who are still undetected and untreated, we have a long way to go toward the control and, ultimately, the eradication of leprosy. I am convinced that as long as the control of leprosy is mainly the responsibility of vertical programs and general medical staff are poorly, if at all, trained in leprosy, the discrepancy between the numbers of estimated and registered patients will remain. Under these circumstances a substantial number of patients, especially those with early symptoms of leprosy, who attend the general medical services may not be recognized as having leprosy. Training of the general medical staff in the basic facts of leprosy is of much importance.

In conclusion, the investment in training is one of the best we can make in the control of leprosy.

- Marijke Becx-Bleuminck, M.D., D.T.P.H.

Director

Leprosy Control Division

All Africa Leproso Rehabilitation Center (ALERT)

P.O. Box 165

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

1. WHO Study Group. Chemotherapy of leprosy control programmes; report of a WHO Study Group. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1982. Tech. Rep. Scr. 675.

2. World Health Organization. Report of a consultation on implementation of multidrug therapy for leprosy control. Unpublished. WHO/LEP/85.1.

3. World Health Organization. Report of the second coordinating meeting on implementation of multidrug therapv in leprosy control programmes. Unpublished. WHO/CDS/LEP 87.2.

4. UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases. Report of the fifth meeting of the scientific working group on the chemotherapv of leprosy. TDR/THELEP-SWG(57)86.3.

5. Rao, C. K. Drugs against leprosy. World Health For. 9(1988)63-67.

6. Mehta, J., Gandhi, I. S., Sane, S. B. and Wamburkan, M. N. Some clinical impressions on multidrug therapy (MDT) in leprosy. Lepr. Rev. 57 Suppl. 3(1986)75-76.

7. Ganapati, R., Revankar. C. R. and Pai, R. Three years of assessment of multidrug therapy in multibacillary leprosy cases. Indian J. Lepr. 59(1987)44-49.

8. Depasquale, G. The Malta experience; Isoprodianrifampicin combination treatment for leprosy. Lepr. Rev. 57 Suppl. 3(1986)29-37.

9. Alvarenga, A. E. Report of a joint leprosy-tuberculosis project in Paraguay. Lepr. Rev. 57 Suppl. 3(1986)53-59.

10. Chum, H. J. The impact of MDT implementation in the Tanzanian National TB-Leprosy Programme. Lepr. Rev. 57 Suppl. 3(1986)63-66.

11. Ji. B., Chen, J., Wang, C. and Xia, G. Hepatotoxicity of combined therapy with rifampicin and daily prothionamide for leprosy. Lepr. Rev. 55(1984)283-289.

12. Cartel, J. L., Millan. J., Guelpa-Lauras, C.-C. and Grosset, J. H. Hepatitis in leprosy patients treated by a daily combination of dapsone, rifampin and a thioamide. Int. J. Lepr. 51(1983)461-465.

13. Waters. M. F. R., Ridley. D. S. and Ridley, M. J. Clinical problems in the initiation and assessment of multidrug therapy. Lepr. Rev. 57 Suppl. 3(1986)92-100.

14. Pattyn, S. R., Janssens, L., Bourland. J., Saylan, T., Davics, E. M., Grillone, S., Feraci, C. and the Collaborative Study Group for the Treatment of Leprosy. Hepatotoxicity of the combination of rifampin-ethionamide in the treatment of multibacillary leprosy. Int. J. Lepr. 52(1984)1-6.

15. Cartel, J.-L., Naudillon, Y., Artus. J.-C. and Grosset, J. H. Hepatotoxicity of the daily combination of 5 mg/kg prothionamide + 10 mg/kg rifampin. Int. J. Lepr. 53(1985)15-18.

16. Alvarenga, A., Leguizamon, O., Frulos, V. and von Ballestrem, W. G. The leprosy eradication program in Paraguay with the combination rifampin-lsoprodian. Int. J. Lepr. 52(1984)7-14.

17. Revankar, D. L. Multidrug therapy cost; a hypothetical analysis. Lepr. Rev. 57(1986)279-285.

18. Cruz. D. M. The future of leprosy in the Dominican Republic: experience with multidrug therapy. Lepr. Rev. 57 Suppl. 3(1986)127-133.

19. World Health Organization. MDT statistics on leprosy. May 1988.

20. Ganapati, R., Revankar, C. R. and Gawade, P. B. Multidrug therapy for multibacillary leprosy-experience in Bombay. In: Proceedings of the XII International Leprosy Congress, New Delhi, February 20-25, 1984. New Delhi: Printaid, n.d., pp. 225-229.

21. Samson, P. D., Ycllapurkar, M. V., Parkhe, S. M. and Solomon, M. Implementation of pulse therapy in Miraj Taluk. In: Proceedings of the XII International Leprosy Congress. New Delhi. February 20-25, 1984. New Delhi: Printaid, n.d., pp. 236-240.

22. Ross, W. F. A process for planning the introduction and implementation of multidrug therapy for leprosy. (Editorial) Lepr. Rev. 58(1987)313-323.

23. Neville, J. After multidrug therapy (MDT) who is responsible for continuing care? (Editorial) Lepr. Rev. 59(1988)1-3.

24. WHO Expert Committee on Tuberculosis. Ninth report. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1974. Tech. Rep. Scr. 552.

25. Kalthoff, P. G. The use of MDT in the three western regions of Nepal. Lepr. Rev. 57 Suppl. 3(1986)106-114.

26. Samuel. N. M., Samuel, S., Nakami, N. and Murmu, R. Multidrug treatment of leprosy -practical application in Nepal. Lepr. Rev. 55(1984)265-272.

27. Birch, M. C. Leprosy treatment in Nepal with multidrug regimens. Lepr. Rev. 55(1984)255-264.

28. All Africa Leprosy and Rehabilitation Training Center (ALERT). Manual for Implementation of Multiple Drug Therapy. Addis Ababa: ALERT, 2nd rev. ed., 1987.

29. Thangaraj, E. S. Multidrug Therapy; Working Guide. London: The Leprosy Mission, 3rd rev. ed., August 1984.

30. Manual for the Implementation of Multi-Drug Therapy in the Leprosy Control Programme of Nepal. November 1985.

31. Manual of the National Leprosy Tuberculosis Programme for the Clinical Officer Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control. Ministry of Health of Kenya, 1987.

32. Manual for the National Tuberculosis/Leprosy Programme in Tanzania for District Tuberculosis/Leprosy Coordinators. 2nd ed., 1987.

33. WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy. Fifth Report. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1977. Tech. Rep. Ser. 607.

34. de Rijk, A. J., Nilsson, T. and Chonde, M. Quality control in leprosy programmes: preliminary experience with inter-observer comparison in routine services. Lepr. Rev. 56(1985)177-191.

35. Georgiev, G. D. and McDougall, A. C. Skin smears and the bacterial index (BI) in multiple drug therapy leprosy control programs: an unsatisfactory and potentially hazardous state of affairs. Int. J. Lepr. 56(1988)101-103.

36. Noordeen, S. K., personal communication.

37. Grosset. J. H. Criteria for determining the exact end of MDT in leprosy. In: Criteria to Determine the Exact End of Multidrug Therapy in Leprosy. Workshop held in Würzburg 17 July 1987. Pritze, S., ed. Würzburg: Armauer Hansen Institute, 1988, p. 11-14.

38. Leiker, D. L. Duration of treatment in multibacillary leprosy with MDT regimens containing rifampicin. In: Criteria to Determine the Exact End of Multidrug Therapy in Leprosy. Workshop held in Würzburg 17 July 1987. Pritze, S., ed. Würzburg: Armauer Hansen Institute, 1988, pp. 15-19.

39. All Africa Leprosy and Rehabilitation Training Center (ALERT). Manual for Out-Patient Treatment of Nerve Damage. Addis Ababa: ALERT, 1st rev. ed., February 1988.

40. Huikeshoven, H. A Spot Test for Dapsone in Urine; Technical Guide for Testing Patient Compliance with Dapsone Intake in Leprosy. Amsterdam: ILEP, n.d.

41. van Asbeck-Raat, A.-M. and Becx-Bleumink, M. Monitoring dapsone self-administration in a multidrug therapy programme. Lepr. Rev. 57(1986)121-127.

42. Becx-Bleumink, M. MDT in the leprosy programme of ALERT-a review. Paper prepared for the Pre-Congress Workshop on Leprosy Control, Evaluation and Integration, XIII International Leprosy Congress, 1988.

43. WHO Study Group. Epidemiology of leprosy in relation to control. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1985. Tech. Rep. Ser. 716.

44. ILEP forms. Questionnaire B, annual report.

45. Rangaraj, M. and Rangaraj, J. Experience with multidrug therapy in Sierra Leone. Lepr. Rev. 57 Suppl. 3(1986)77-91.

46. Palande. D. D. and Ramu, G. Multidrug therapy(in India); report of an information get together of leprologists involved in MDT in India. 1987. Int. J. Lepr. 56(1988)120-121.

47. Reddy, N. B. B. Why classify leprosy patients into paucibacillary and multibacillary groups? (Letter) Lepr. Rev. 58(1987)89.

48. Leprosy Control Department. All Africa Leprosy and Rehabilitation Center (ALERT). Annual Report for 1987. Addis Ababa: ALERT, pp. 70-134.

49. Grosset, J. H., Ji, B. and Ito, T. The First Joint THELEP-Sasakawa Memorial Health Foundation Workshop on Experimental Chemotherapy of Leprosy. Int. J. Lepr. 55 Suppl.(1987)807-813.

50. Jopling. W. H. A report on two follow-up investigations of the Malta-Project. Lepr. Rev. 57 Suppl. 3(1986)47-52.

51. Pattyn, S. R., Groenen, G., Bourland, J., Grillone. S., Janssens, L. and the Collaborative Study Group for the Treatment of Leprosy in Zaire and Rwanda. A controlled therapeutical trial in paucibacillary leprosy comparing a single dose of rifampicin followed by 1 year of daily dapsone with 10 weekly doses of rifampicin. Lepr. Rev. 58(1987)349-358

52. Discussion during workshop. In: Criteria to Determine the Exact End of Multidrug Therapy in Leprosy. Workshop held in Würzburg 17 July 1987. Pritze, S., ed. Würzburg: Armauer Hansen Institute. 1988, p. 54-80.

53. Grosset, J. H. Recent developments in the field of multidrug therapy and future research in chemotherapy in leprosy. Lepr. Rev. 57 Suppl. 3(1986)223-234.

54. Leiker, D. L., Dhople. A. M. and Freerksen, E. Final bulletin. Lepr. Rev. 57 Suppl. 3(1986)274-277.

55. Becx-Bleumink, M. Operational aspects of the implementation of multidrug therapy at ALERT. Ethiopia. Lepr. Rev. 57 Suppl. 3(1986)1 15-123.

56 Ridley, M. J. The disintegration of M. leprae. In: Criteria to Determine the Exact End of Multidrug Therapy in Leprosy. Workshop held in Würzburg 17 July 1987. Pritze, S., ed. Würzburg: Armauer Hansen Institute, 1988, pp. 39-44.

57. Leprosy Unit, Royal Tropical Institute. Management of leprosy control. Participants handbook, exercise book, facilitators' guide. Amsterdam: Royal Tropical Institute, 1988.

58. Wiseman, L. A. Calendar (blister) packs for multidrug therapy in leprosy: an inexpensive locally produced version. (Letter) Lepr. Rev. 58(1987)85-87.

59. Becx-Bleumink, M. Multiple drug therapy: implications for field work and training at ALERT. Lepr. Rev. 57 Suppl. 3(1986)69-80.

60. Wheate, H. W. and Harris, G. F. Operational problems in leprosy programmes when endemicitv declines. (Editorial) Lepr. Rev. 58(1987)1-5.

61. Lechat. M. F. Leprosy: the long hard road. World Health For. 9(1988)69-71.

62. World Health Organization. Report of the consultation on disability prevention and rehabilitation in leprosy. Unpublished. WHO/CDS/LEP/87.3.

63. Leprosy Control Department, All Africa Leprosy and Rehabilitation Center (ALERT), unpublished data. 1988.

64. Feenstra, P. and Tedla. T. A broader scope for leprosy control. World Health For. 9(1988)53-58.

65. World Health Organization. Report of a consultation of leprosy control through primary health care. Unpublished. WHO/CDS/LEP/86.3.

66. Becx-Bleumink, M. New developments in ALERT leprosy control programme and the issues of integration. Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 1(1984)49-55.

67. Toman, K. What are the standard regimens currently used? In: Tuberculosis Case-Finding anil Chemotherapy: Questions anil Answers. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1979, pp. 113-115.

68. Styblo. K. Overview and epidemiological assessment of the current global tuberculosis situation, with emphasis on tuberculosis control in developing countries. Bull. IUATLD 63(1988)39-44.

69. Toman, K. What is the significance of default in chemotherapy of tuberculosis? In: Tuberculosis Case-Finding and Chemotherapy: Questions and Answers. Geneva: World Health Organization. 1979, pp. 211-216.

70. Hertroijs, A. R. A study of some factors affecting the attendance of patients in a leprosy control scheme. Int. J. Lepr. 42(1974)419-427.

71. Lowe. S. J. M. and Pearson. J. M. H. Do leprosy patients take dapsone regularly? Lepr. Rev. 45(1974)218-223.

72. Nigam. P., Siddique, M. I. A., Pandey, N. R., Awasthi, K. N. and Sriwastwa. R. N. Irregularity of treatment in leprosy patients: its magnitude and causes. Lepr. India 51(1979)521-532.

73. Grosset, J. New knowledge on MDT for leprosy control programs gathered since the WHO Study Group recommendation, unpublished paper, 1985.

74. Langhorne, P., Dulfus, P., Berkeley, J. S. and Jesudasan, K. Factors influencing clinic attendance during the multidrug therapy of leprosy. Lepr. Rev. 57(1986)17-30.

75. Subcommittee on Clinical Trials of the Chemotherapy of Leprosy(THELEP)and the Scientific Working Group of the UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Disease. The THELEP controlled clinical drug trials. Int. J. Lepr. 54 Suppl.(1986)864-871.

76. Katoch, K., Sreevatsa. Ramanathan, U. and Ramu, G. Pyrazinamide as part of combination therapy for BL and LL patients-a preliminary- report. Int. J. Lepr. 56(1988)1-9.