- Volume 68 , Number 4

- Page: 426–33

Immuno-histopathology in the diagnosis of early leprosy

ABSTRACT

The present study of 45 early leprosy cases in an endemic area in China indicates: a) Sensitivity of acid-fast bacilli (AFB) detection can be significantly improved by examining approximately 30 serial sections. AFB and/or phenolic glycolipid-I (PGL-I) were mostly detected in the infiltrates in the subepidermal zone, intraneurium, perineurium and around blood vessels. b) PGL-I antigen was positive in 10 clinically suspected, single lesion leprosy cases and AFB positive in 7 patients, AFB and/or PGL-I in nerve in 6 patients. c) Nonspecific chronic inflammation in indeterminate leprosy presented as selective perineural and/or intraneural infiltration with lymphocytes predominating. In the infiltrating mass, fragments of neural tissue were demonstrated with anti-S-100 protein staining. d) Except for 3 cases with unknown numbers of lesions, the present positive immuno-histopathological findings are in direct correlation with the number of lesions at first diagnosis, namely: 41.6% (10/24) for single lesion, 66.6% (6/9) for 2 lesions, and 88.8% (8/9) for patients with >3 lesions. e) Typical epithelioid or macrophage granuloma formations were not seen in early leprosy with a single lesion. In testing the immunological inclination of these patients with CD68 or tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) a positive test is likely to be of prognostic value since TNF-α is involved in granuloma formation and nerve damage.RÉSUMÉ

Cette étude portant sur 45 cas débutants de lèpre dans une région endémique de Chine indique que : (a) La sensibilité de détection des bacilles acido-alcoolo-résistants (AAR) peut être améliorée de façon signifcative par l'examen d'environ 30 coupes sériées. Les bacilles AAR et/ou le glycolipide phénolique I (PGL-I) furent détectés principalement dans les infiltratas de la zone sous-épidermique, intra-neuraux, péri-neuraux et autour des vaisseaux sanguins. (b) L'antigène PGL-I fut détecté chez 10 cas cliniquement suspects de lèpre à lésion unique, des bacilles AAR chez 7 cas et des bacilles AAR et/ou PGL-I dans les nerfs de 6 patients. (c) L'inflammation chronique non spécifique typique de la lèpre indéterminée était caractérisée dans cette étude par un infiltrat à prédominance lymphocytaire présent sélectivement en situation péri neurale ou intra neurale. Dans les masses inliltrées de localisation équivoque, des fragments de tissu nerveux furent démontrés par immuno-marquage à la protéine S-100. (d) A l'exception de 3 cas non considérés parce qu'ayant un nombre indéterminé de lésions, les résultats immuno-histopathologiques présentés ici sont directement corrélés au nombre de lésions lors de l'établissement du diagnostic, à savoir : 41,6% (10/24) pour une lésion unique, 66,6% (6/9) pour 2 lésions et 88,8% (6/9) pour les patients de 3 lésions et plus. (e) La formation de granulomes épithélioïdes ou macrophagiques typiques ne fut pas observée dans les cas de lèpre débutante présentant une lésion unique. L'inclination immunologique de ces patients, testée à l'aide de marqueurs tels CD-68 et le facteur de nécrose tumoral alpha (TNF-α), pourraient avoir une valeur pronostique si positifs puisque TNF-α est impliqué dans la formation des granulomes et les lésions nerveuses.RESUMEN

Se realizó el estúdio de 45 casos de lepra temprana en una region de China con lepra endémica. Las conclusiones del estudio fueron: a) La detección de bacilos ácido resistentes (BAAR) puede mejorarse significativamente si se examinan aproximadamente 30 secciones seriadas; los BAAR y/o el glicolípido fenólico-I (PGL-I) se detectaron principalmente en el infiltrado de las zonas sub-epidérmica, del intraneurio, del perineurio, y alrededor de los vasos sanguíneos. b) El PGL-I fue positivo en 10 casos con sospecha clínica de la enfermedad y 7 de los casos fueron positivos para BAAR; en los nervios de 6 pacientes se encontraron BAAR y/o PGL-I. c) La inflamación crónica no específica en la lepra indeterminada se presentó como un infltrado perineural o intraneural selectivo con predomínio de linfocitos. En el infiltrado se encontraron fragmentos de tejido neural utilizando un anticuerpo contra la proteína S-100. d) Excepto por 3 casos con números desconocidos de lesiones, los presentes hallazgos inmunohistopatológicos correlacionaron de manera directa con el número de lesiones en el primer diagnóstico, especificamente: 41.6% (10/24) para lesiones únicas, 66.6% (6/9) para 2 lesiones, y 88.8% (8/9) para pacientes con >3 lesiones. e) En los casos de lepra temprana con una sola lesion no se observaron granulomas epitelioides o macrofágicos típicos. Si se probara el estado inmunológico de estos pacientes con CD68 o factor de necrosis tumoral alfa (TNFα), es probable que una prueba positiva pudiera ser de valor pronóstico, ya que el TNFα participa en la formación de granulomas y en el dano a nervios.The diagnosis of early leprosy, especially single-lesion leprosy, based upon clinical and skin-smear examinations is often difficult under field conditions. Routine histopathologic examination with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and acid-fast staining requires 20-30 or more serial sections for the detection of acid-fast bacilli (AFB) and perineural/intraneural inflammatory changes (5). It has been reported that the demonstration of Mycobacterium leprae-specific phenolic glycolipid-I (PGL-I) antigen increases the sensitivity of the diagnosis (4), and the use of neural antigen S-100 protein enhances the histologic diagnosis of early neural involvement in skin biopsies (3). The present study involves suspected early lesions identified during leprosy surveys in endemic townships in Wenshan Prefecture, Yunnan Province, China. In addition, cytokines CD68 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) were applied to selected tissue sections to study the possibility of further immuno-histopathologic developments in these cases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

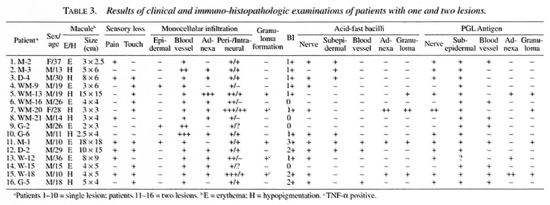

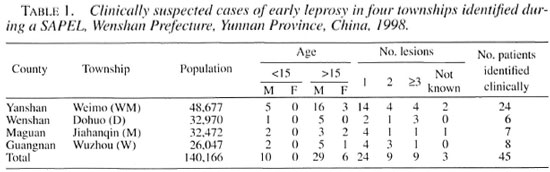

Wenshan Prefecture, Yunnan Province, is one of the most endemic areas for leprosy in China. The average annual detection rate was 3.8/100,000 and prevalence was 7.8/10,000 between 1981-1985, just before the implementation of the World Health Organization recommended multiple drug therapy (WHO/MDT) (7). During 1998, a SAPEL (13) was conducted in selected townships from four counties of Wenshan known to be of high endemicity in an attempt to integrate leprosy control into the primary health system. After intense health education of the village people and brief training of primary health workers, suspected cases were re-examined by an experienced leprosy worker (S.P. Ran), biopsies and smears taken, and a tentative clinical diagnosis was made at the township health center. Each township has about 20,000-30,000 population and a total of 45 suspected leprosy cases were examined by immuno-histopathology (Table 1).

The direct immunoperoxidase method with strepto-avidin-biotin complex (1) was used for the following antibodies: 1) monoclonal antibody against PGL-I (DZ-1; from J. T. Douglas, Microbiology Department, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S.A.); 2) rabbit anti-S-100 protein (Zymed Laboratories, Inc., San Francisco, California, U.S.A.); 3) monoclonal mouse anti-human macrophage CD68 (Zymed); 4) anti-human TNF-α neutralizing antibody (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S.A.).

In addition, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histopathology and Fite's method for acid-fast staining were used for M. leprae. Tests were performed on 5-µm thick sections from paraffin-embedded skin tissue.

The histopathological diagnosis of leprosy was made if the biopsy specimen met the criteria of AFB and/or PGL antigen in the tissue and was supported by selective perineural and intraneural mononuclear cell infiltration and/or granuloma formation (14).

RESULTS

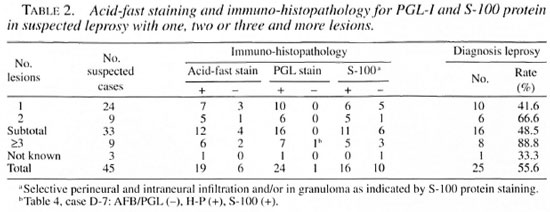

The results in Table 2 indicate that 55.6% (25/45) of the confirmatory diagnosis may be made in early leprosy with PGL and S-100 staining. There is a direct correlation between the number of lesions and the confirmatory rate in early leprosy. The positive rate for acid-fast staining is 25% (4/16) in patients with 1 or 2 lesions, if relying on 6-8 sections only. AFB positivity reached 75% (12/16) after examining about 30 successive serial sections. PGL staining is more sensitive than the acid-fast technique for leprosy bacilli (24 versus 19). PGL antigen positivity plus perineural and/or intraneural inflammation in biopsied tissue indicate leprosy.

PGL-1 antigen was demonstrated in the tissue sections of 16 patients with 1-2 lesions; after examination of 30 successive sections, 12 were AFB positive. Only 1-3 AFB were seen inside the nerve (Fig 1). More patients with two lesions were positive for AFB/PGL than patients with only one lesion (Table 3). AFB and/or PGL antigen were located mainly in the infiltrates in the subepidermal zone, intraneurium, perineurium and around blood vessels (Fig. 2). AFB may be seen inside nerves in 62.5% (10/16) and PGL antigen in 68.8% (11/16) of patients with 1-2 lesions.

Fig. 1. Patient M-2 (single lesion). Bacilli in nerve (acid-fast stain ×1000).

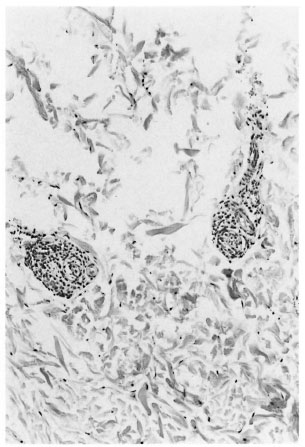

Fig. 2. Patient G-5. PGL antigen inside nerve in early leprosy (PGL-I stain ×400).

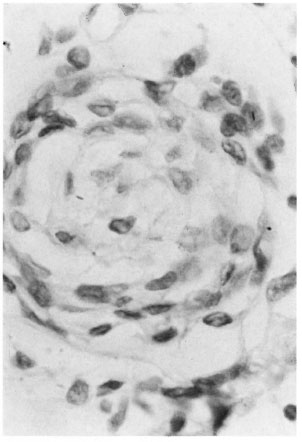

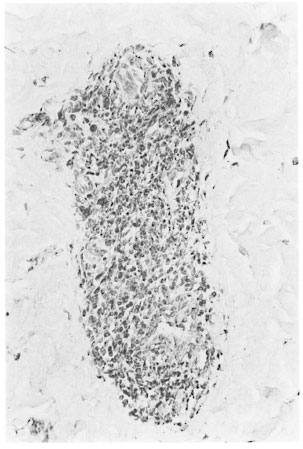

Selective perineural/perineural inflammation was present in all 10 single-lesion cases; whereas only 6 of 10 showed intraneural changes (Figs. 3 and 4, Table 1). Early granuloma formation appeared in 5 patients with 1-2 lesions. Staining for TNF-oc was done for 12 patients from WM Village. Four patients (WM-20 single lesion; WM-12 and WM-18 each 2 lesions; WM-19 >3 lesions) were positive forTNF-α (Fig. 5). Activated macrophages as indicated by CD68 (Fig. 6) and fNF-a were demonstrated in nerve granuloma.

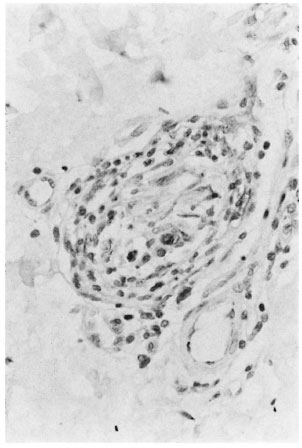

Fig. 3. Patient M-2 (single lesion). Selective intraneural and perineurial infiltration (H&E ×200).

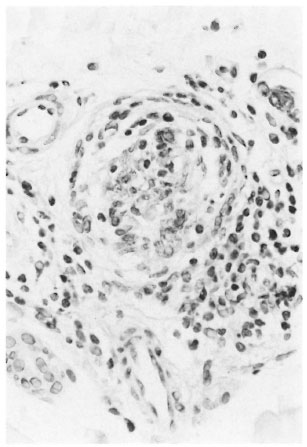

Fig. 4. Patient M-2 (single lesion). Intraneural and perineurial infiltration (S-100 protein stain ×400).

Fig. 5. Patient WM-20 (single lesion). TNF-α in nerve granuloma (TNF-α stain ×200)

Fig. 6. Patient WM-19 (three lesions). Activated macrophages in granuloma (CD68 stain ×400).

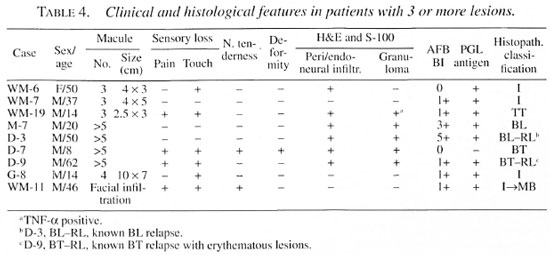

Table 4 indicates that AFB positivity and granuloma formation were seen more in patients with >3 lesions. Combining the histopathological findings in Tables 2 and 3, it is apparent that confirmatory diagnosis with immuno-histopathology is indispensable in early leprosy, especially in patients with a single lesion.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, confirmatory diagnosis was made in suspected early leprosy with a few macular lesions except WM-11 who had mild diffuse facial infiltration and a bacterial index (BI) of 1+ by positive AFB/PGL and involvement of dermal nerves by immuno-histopathology. Only patient D-7 had granuloma but was AFB and PGL negative, indicating borderline tuberculoid (BT) leprosy clinically. Sensitivity in AFB detection can be significantly improved by examination of up to 30 or more serial sections.

Detection of PGL with immuno-peroxidase staining can greatly enhance the sensitivity of histologic diagnosis of early leprosy and does not require additional tissue sections. In the present study, five patients with perineural and/or intraneural inflammation were PGL positive and AFB negative (WM-16, WM-21, G-2, WM-15, WM-6); similar findings were also reported by others (4, 9). If only PGL antigen in the subepidermal zone or perineural infiltrate can be found, the diagnosis of leprosy cannot be made.

AFB and/or PGL were mostly located in the subepidermal zone, perineural and intraneural infiltration, and also around blood vessels. No AFB/PGL were detected in the epidermis or arrector pili muscles. Most leprosy histologists have emphasized the fact that AFB/PGL inside nerve is significant for the diagnosis of early leprosy (2, 5, 11, 14). In the present study, only 6 of 10 patients with single-lesion leprosy were PGL/AFB-positive in nerve, similar to Job, et al.'s findings in indeterminate leprosy (5).

PGL staining in the subepidermal zone can be confused with incontinence (or dropping out) of pigment from the basal layer of the epidermis (11) which is stained brown by diamino-benzidine (DAD). Technically, this may be overcome in the future by avoiding DAD in substrate staining or by staining for decoloration to remove melanin (12).

In indeterminate leprosy, lympho-histiocytic infiltration usually occupies less than 10% of the dermis. For single-lesion leprosy, mild intraneural and perineurovascu- lar inflammation can be seen, but without significant granuloma formation (8, 11, 14). It is of interest that with S-100 protein staining, nonspecific chronic inflammation in indeterminate leprosy may present as selective perineural and/or intraneural infiltration, with lymphocytes predominating. In the infiltratory mass fragmented nerve may be seen. S-100 protein staining aids the visualization of perineural and intraneural changes of cutaneous nerves and nerve fragments inside granuloma. Early granuloma formation was demonstrated in 2 out of 10 cases with single-lesion leprosy. The amount of AFB or PGL antigen inside nerve does not appear to be correlated with the intensity of nerve inflammation.

What is early leprosy? The WHO emphasized that the number of lesions should be limited, infiltration mild and with no granuloma formation (14). In China, it is emphasized that in early leprosy the duration of illness should be less than 2 years and without deformity. The positive correlation between number of lesions and positive immunohistology, the number of lesions and density of M. leprae or PGL in tissue sections as well as granuloma confirmation are presented in the present study. TNF-α can be demonstrated in five patients with nerve granuloma formation (Tables 3 and 4). Further study is necessary to understand TNF-α involvement in granuloma formation and nerve damage (6, 10).

In the present study, clinically suspected early leprosy with hypopigmented or erythematous macules demonstrated perineu- rovascular and/or perineural inflammation in biopsies. These changes are usually reported as nonspecific chronic inflammation (NSCI). If both AFB and PGL are negative, or only perineural infiltrate can be seen, a definite diagnosis of leprosy cannot be made. The possibility of NSCI preceding indeterminate leprosy has already been pointed out (5).

It is worthwhile to follow up suspected early leprosy with NSCI every 3-6 months for 1 or more years before reaching a conclusive diagnosis.

Acknowledgment. This study is supported by grants from The Heiser Program for Research in Leprosy and Tuberculosis.

REFERENCES

1. Elias, J. M., Margiotta, M. and Gabore, D. Sensitivity and detection efficiency of the peroxidase (PAP), avidin-biotin complex (ABC) and peroxidase-labeled avidin-biotin (LAB) methods. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 92 (198) 62-67.

2. Fine, P. E. M., Job, C. K., Lucas, S. B., Meyers, W. M., Ponnighaus, J. M. and Sterne, J. A. C. Extent, origin, and implications of observer variation in the histopathological diagnosis of suspected leprosy. Int. J. Lepr. 61 (1993) 270-282.

3. Fleury, R. N. and Bacchi, C. E. S-100 protein and immunoperoxicase technique as an aid in the histopathological diagnosis of leprosy. Int. J. Lepr. 55 (1987) 338-344.

4. Goto, M. and Izumi, S. Light- and electron-microscopic immunohistochemistry using anti-PGL-I antibody specific for Mycobacterium leprae. (Abstract) Int. J. Lepr. 59 (1991) 195.

5. Job, C. K.. Baskaran, B., Jayakumar, J. and Aschhoff, M. Histopathological evidence that indeterminate leprosy may be a primary lesion of the disease. Int. J. Lepr. 65 (1997) 442-449.

6. Khanolkar-Young, S., Rayment, N., Brickell, P. M, Katz, D. R., Vinayakumar, S., Colston, M. J. and Lockwood, D. N. J. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) synthesis is associated with the skin and peripheral nerve pathology of leprosy reversal reactions. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 99 (1995) 196-202.

7. Li, H. Y., Weng, X. M., Li, T., Zheng, D. Y., Mao, Z. M., Ran, S. P. and Liu, F. W. Long-term effect of leprosy control in two prefectures of China, 1955-1993. Int. J. Lepr. 63 (1995) 213-221.

8. Liu, T. C., Yen, L. Z., Ye, G. Y. and Dung, G. J. Histology of indeterminate leprosy. Int. J. Lepr. 50 (1982) 172-176.

9. Natrajan, M., Katoch, K., Katoch, V. M. and Bharadwaj, V. P. Enhancement in the histological diagnosis of indeterminate leprosy by demonstration of Mycobacterium antigens. Acta Leprol. 94 (1995) 201-207.

10. Ottenhoff, T. M. Immunology of leprosy: lessons from and for leprosy. Int. J. Lepr. 62 (1994) 108-121.

11. Ridley, D. S. Skin Biopsy in Leprosy: Histological Interpretation and Clinical Application. 3rd edn. Basle: GIBA Geigy Ltd., 1990.

12. Wang, B. Y., Huang, G. S. and Zhang, Y. G. Techniques in Histopathology. Beijing: People Health Press, 2000.

13. World Health Organization. Leprosy Elimination Campaigns (LEC) and Special Action Projects for the Elimination of Leprosy (SAPEL): Questions and Answers. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1997.

14. World Health Organization. WHO consultation on early diagnosis of leprosy. May 1990. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1990.

1. M.D.; Beijing Tropical Medicine Research Institute, 95 Yong-An Road, Beijing 100050, China.

2. M.D., M.P.H., Beijing Tropical Medicine Research Institute, 95 Yong-An Road, Beijing 100050, China.

3. Department of Pathology, Beijing Friendship Hospital, Beijing 100050, China.

4. M.D., Department of Pathology, Beijing Friendship Hospital, Beijing 100050, China.

5. M.D., Director, Wenshan Prefectural Institute of Dermatology, Wenshan Prefecture, Yunnan Province 663000, China.

Reprint requests to Dr. Li at the above address or FAX 86-10-63023261; email: lihy@bj.col.com.cn

Received for publication on 28 February 2000.

Accepted for publication in revised form on 25 October 2000.