- Volume 66 , Number 2

- Page: 149–58

The occurrence of reactions and impairments in leprosy: experience in the Leprosy Control Program of three provinces in Northeastern Thailand, 1978-1995. I. Overview of the study

ABSTRACT

Aim: This paper is the first in a series of three reports on the occurrence of reactions and impairments in leprosy in Thailand. This first paper gives a general overview about the methodology of the study, some epidemiological observations, delay in detection, multidrug therapy (MDT) completion rates and relapses. The other two papers report on: II. Reactions and III. Neural and Other Impairments. This study was carried out f rom 1987 until 1995 in three neighboring provinces in northeastern Thailand. Study design: A population-based, prospective cohort study. Study population: All 640 newly diagnosed leprosy patients in the three provinces, registered between October 1987 and September 1990, were included [420 paucibacillary (PB) and 220 multibacillary (MB)] . This group was followed up (actively and passively) until the end of 1995. Methods: Patients were found by active and passive case finding. All new, untreated leprosy patients f rom the area were enrolled and started on the World Health Organization (WHO) MDT (WHO/MDT) regimen. A vertical control service was run by specialized leprosy workers. During treatment the patients received their monthly doses at home. During surveillance the patients were followed up once a year by a special team. Patients were questioned about delay in detection. Treatment completion rates were calculated. The occurrence of reactions and neural and other impairments at the beginning of, during and after treatment was ascertained. After treatment, the occurrence of late reactions and relapses was recorded. Results: A higher frequency of leprosy was found among the male patients, especially in the MB group. However, in the PB group a higher female/male ratio was found in the age group 55 years and older. There was an increase in the detection rate f rom the youngest age group to the age group 55 years and older, which showed the highest detection rate. Treatment completion rates were high, 95% in both in the PB and MB treatment groups. About 50% of the new cases reported a delay between onset and registration of 1 year or more. By 1995, 93% of the original patient group was still available for follow up. By the end of 1995, 8 PB and 2 MB relapses were recorded.RÉSUMÉ

But: Cet article est le premier d'une série de trois, traitant de la fréquence d'apparition de réactions et de complications invalidantes de la lèpre en Thaïlande. Ce premier article expose les grandes lignes sur la méthodologie de l'étude, certaines observations épidémiologiques, les délais de détection, ainsi que le taux de traitement polychimiothérapeutique (PCT) complet et le nombre de rechutes. Les deux autres articles rapportent: II. Les états réactionnels et III. Les atteintes nerveuses et autres atteintes. Cette étude s'étend de 1987 à 1995 sur 3 provinces contigues de la partie nordest de la Thaïlande. Type d'étude: Etude prospective par cohortes, basée sur une population. Population d'étude: La totalité des 640 nouveaux cas de lèpre [420 paucibacillaires (PB) et 220 multibacillaires (MB)] diagnostiqués dans les 3 provinces, enregistrés de octobre 1987 à septembre 1990. fut passivement et activement suivie jusqu'à lin 1995. Méthode: Les patients furent trouvés par recherche à la fois active et passive. Tous les nouveaux patients non traités atteints de lèpre, provenant de la zone choisie furent enrôlés dans l'étude et mis sous traitement polychimiothérapeutique (PCT) reeommendé par l'Organisation mondiale de la Santé (PCT/OMS). Un service de contrôle vertical lut mis sur pied et maintenu par des léprologistes spécialisés. Durant le traitement, les patients ont reçu leurs doses mensuelles à la maison. Durant la période de suivi après le traitement, les patients ont été examinés une fois par an par une équipe spécialement mise sur pied à cet effet. Pour chaque patient, on a demandé de spécifier leur délai de détection. Les taux de traitement complet furent calculés. L'apparition d'états réactionnels et de complications invalidantes nerveuses et autres fut dépistée et vérifiée en début, pendant, et après le traitement. Après le traitement, l'apparition d'états réactionnels tardifs et de rechutes a été enregistré. Résultats: Une plus grande fréquence de lèpre a été observée parmi les patients masculins, particulièrement dans le groupe MB. Cependant, parmi le groupe PB, le ratio femme/homme était plus élevé dans la classe d'âge de 55 ans et plus. Il y avait une augmentation du taux de détection de la plus jeune classe d'âge à la classe d'âge de 55 ans et plus, ces derniers montrant le meilleur taux de détection. Le taux de traitement complet était élevé, étant de 957r tant dans le groupe PB que le groupe MB ayant reçu le traitement. Environ 50% des nouveaux cas présentaient un délai d'un an ou plus entre l'apparition de symptômes et l'enrôlement dans l'étude. En 1995, 937c du groupe originel de patients était encore présent pour le suivi. Fin 1995, 8 rechutes de cas PB et 2 rechutes de cas MB ont été enregistrées.RESUMEN

Objetivo: Este es el primero de tres artículos sobre la occurrencia de reacciones y el empeoramiento consecuente de la lepra en pacientes de Tailandia, liste primer artículo es una visión general de la metodología del estudio, algunas observaciones epidemilógicas, las causas del retardo en la detección de casos, las tasas de cumplimiento en el tratamiento, y las tasas de recaída. Los otros dos artículos se refieren a las reacciones en la lepra (II) y a las alteraciones neurológicas y de otro tipo (III). El estudio se efectuó de 1987 a 1995 en tres provincias vecinas del noreste de Tailandia. Diseño del estudio: Se trata de un estudio poblacional prospectivo de cohortes. Población de estudio: Los 640 casos nuevos de pacientes con lepra [420 paucibacilares (PB) y 220 multibaeilares (MB)| diagnosticados en tres provincias de Tailandia entre Octubre de 1987 y Septiembre de 1990. El seguimiento de los pacientes se continuó hasta finales de 1995. Métodos: Los pacientes se descubrieron utilizando métodos activos y pasivos de búsqueda. Todos los pacientes nuevos no tratados del área se incluyeron en el estudio y se sujetaron al esquema de tratamiento con poliquimioterapia (PQT) sugerido por la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). El control vertical del estudio fue realizado por trabajadores especializados de la lepra. Durante el tratamiento los pacientes recibieron sus dosis mensuales de PQT en sus domicilios. Durante el seguimiento los pacientes se examinaron una vez al año por un equipo especializado de leprólogos. Los pacientes se interrogaron para conocer las razones de su retardo en su detección, se calcularon las tasas de cumplimiento del tratamiento, se registraron las tasas de los cuadros reaccionales y de las alteraciones neurológicas y de otro tipo, al inicio, durante y después del tratamiento. Finalmente se registraron la occurrencia de reacciones tardías y la tasa de recaídas. Resultados: Se encontró una alta frecuencia de lepra en la población masculina del grupo MB. Por el contrario, en el grupo PB predominaron los casos femeninos, sobre todo entre los pacientes de 55 años y mayores. La tasa de detección de casos aumentó del grupo de edad más joven al grupo de pacientes de 55 años y mayores los cuales constituyeron el mayor número de casos. Las tasas de terminación del tratamiento fueron altas (95%) tanto en el grupo MB como en el PB. Casi el 50% de los casos declararon que hubo un lapso de un año o más entre la aparición de los primeros síntomas y el descubrimiento de su enfermedad. Para 1995, la mayoría de los pacientes (93%) del grupo original todavía pudieron ser examinados. A finales de 1995 se registraron recaídas en 8 casos PB y en 2 MB.The multidrug therapy (MDT) regimens in leprosy are generally considered to be highly effective and well tolerated. The ultimate test of chemotherapeutic effectiveness is the relapse rate among patients who have completed a prescribed course of the treatment (1). The ultimate test of a leprosy control program's effectiveness is the prevalence of impairments among newly diagnosed patients and the occurrence of new/additional (N/A) impairments among patients on treatment and after treatment(20, 25). Impairment is a very relevant measurement of progress in leprosy control (22). In evaluating any new treatment regimen, the incidence of impairments during and after treatment is perhaps as important a measure of the value of a new regimen as the relapse rate (25)

A major problem in leprosy is the development of immunological reactions and, in particular, the loss of peripheral nerve function, which usually develops during reactions. Type 1 reaction is one of the major causes of nerve damage in leprosy (14). These reactions and the potential loss of nerve function can occur at any time in the disease process: before the start of treatment, during treatment and even after treatment. Nerve-function impairment (NFI), if not diagnosed and treated in time, may become permanent and may result in disabilities and handicaps (3).

This is the first in a series of three papers and gives a general overview of a study from Thailand, its methodology, epidemiological observations, delay in case detection, MDT completion rates and relapses. The other two papers report on the occurrence of reactions (II. Reactions) and impairments (III. Neural and Other Impairments). It is a population-based, prospective cohort study implemented under field-program conditions (albeit a vertical leprosy service run by a specialized leprosy control staff) with extra input from the Regional Leprosy Control Center.

The area chosen for the study consisted of three neighboring provinces, Mahasarakham, Roi-et and Kalasin, in northeastern Thailand. These provinces were among the few specialized program areas still maintained in Thailand at that time (19). The same routine control activities, including passive and active case finding, had been going on in this area for many years. MDT, according to the 1982 recommendations of the WHO, was introduced in 1984/1985 (4, 29). In 1989, the total population of these provinces was 2,980,000; the registration rate was 2 per 10,000 and the case detection rate 8 per 100,000. The Regional Leprosy Control Center is in Khon Kaen, the administrative center of Region 6 in northeastern Thailand.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

All newly diagnosed leprosy patients, never treated before, from these three provinces registered from October 1987 until September 1990 were included in this study. The patients were actively followed up until released from surveillance. The study lasted until the end of 1995.

Case finding was by both active and passive methods. The leprosy control staff were requested to refer new patients for confirmation of diagnosis and classification and, in case of problems or complications, to monthly referral clinics at the provincial health offices. A team from the regional Leprosy Control Center, Khon Kaen, attended those clinics. Leprosy field workers visited the patients at home for the supervised part of the treatment (WHO/MDT regimen) once a month. Other special teams were responsible for rapid village surveys (RVS) and for the annual examination of each patient released from treatment (RFT).

Paucibacillary (PB) patients were all under active surveillance for 3 years and passive surveillance until the end of the study. It is estimated that the average surveillance period for PB patients was 5 years, fvlultibacillary (MB) patients enrolled in the first 15 months of the enrollment period would (if provided with the minimum 24 months of WHO/MDT because of a negative smear at RFT) have had 5 years of active surveillance. MB patients enrolled from January 1989 until September 1990 would not be able to complete 5 year of active surveillance within the study period. It is, therefore, estimated that the average surveillance period for MB patients was 3 years.

Skin smears were taken from all new patients at release from treatment and, additionally, once a year during treatment and during surveillance of MB patients. Biopsies were only taken in special cases. At the time of diagnosis, the patients were interviewed about the duration of their illness before registration as a leprosy patient. From this interview the time delay in case detection was calculated.

Nerve-function assessments were supposed to be made monthly and impairment records (27) every 3 months. In case of complications, recordings were made monthly. To ensure the quality of the impairment examination and recording in this study, a special prevention of disability (POD) team from the Leprosy Control Center, Khon Kaen (consisting of a physiotherapist and a rehabilitation assistant) visited patients at their homes for re-examination, at least once during treatment and once during surveillance.

The disease was classified either as PB or MB leprosy according to WHO guidelines (29). Additional criteria in this study were: a) clinically borderline tuberculoid (BT) patients with a negative skin smear but with 10 or more skin lesions were assigned to the MB group; b) clinically borderline lepromatous (BL) patients with repeatedly negative smears were reclassified as BB. Adequate treatment, PB MDT and MB MDT, was defined according to WHO guidelines (29). During this study, patients who were still skin-smear positive after 24 doses of WHO/MDT continued with WHO/MDT until smear negativity. As an outcome indicator for treatment compliance, the treatment completion (TC) rate was calculated: the total number of patients who took their WHO/MDT within the prescribed period divided by the total number of patients in the cohort (all patients who were enrolled in this study). Those MB patients who finished 24 doses within 36 months were recorded as TC, even though some of them continued treatment (until smear negative) after completing 24 doses.

Reversal reactions (RR) and erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) reactions were differentiated into mild and severe reactions (for definitions see II. Reactions). In this study only severe reactions at the start of and while on treatment were recorded. However, after RFT both mild and severe reactions were taken into account in order to differentiate late reaction from relapse. Criteria for a relapse were: a) after RFT the appearance of new lesions or an increase in size of old lesions; b) skin smear becoming positive in a previously PB patient (or MB patient who had a negative smear from the start) or an increase in BI of more than 1 in a previously skin-smear positive patient (1).

History taking; inspection of eyes, hands and feet; palpation of the nerves; voluntary muscle testing (VMT) and sensory testing (ST) provided the relevant information needed for the early diagnosis of NFI. As a sensory test the ballpoint pen test (27) was used. Semmes-Weinstein nylon monofilaments were only introduced in the referral clinics in 1992. In this study the WHO three-grade disability system was followed with a few exceptions (28).

Statistical methods used were: the normal test (large samples) to determine the difference between two unpaired observations (difference between two means) (11) and the chi-squared test to analyze the difference between proportions and for trends (Epi Info software, version 6).

RESULTS

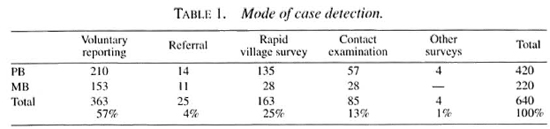

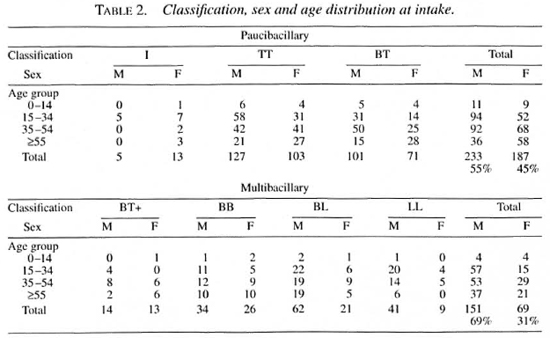

A total of 640 leprosy patients were included in the study: 420 (66%) PB and 220 (34%) MB, 384 (60%) males and 256 (40%) females; 28 (4%) children (0-14 years old at the time of diagnosis) and 612 adults (15 years and older); 61 % were found by voluntary reporting (including referrals) and 39% by active case finding (rapid village survey, contact examination, other surveys) (Table 1). No case was registered with pure neuritic leprosy (Madrid classification) (Table 2). Mean age at detection was 39.9 years

Classification, sex and age distribution at diagnosis. Over the years among new patients a higher PB than MB proportion was found in the area (data not shown). However, a gradual increase in the proportion of MB disease has been reported (19). The PB proportion by passive case finding was 58%; PB proportion by active case finding 78% (Table 1). A higher frequency of leprosy was found in male adults, especially in the MB group (statistically significant), particularly noticeable in BL and LL leprosy (Table 2). There was one exception to the higher male/female ratio in our study: in the PB group in the age group 55 and older there was a higher female/male ratio (highly significant, p <0.001), even if we take the higher number of females in the older age groups into account (age groups 55 and older in the three provinces in 1990 census: 132,270 males and 152,694 females). The higher numbers of female leprosy patients in those age groups were mainly from voluntary reporting. In both the PB and MB groups the highest proportions (statistically significant) of cases detected were: in men, in the age groups 15-34 and 35-55 years old; in women, in the age groups 35-55 and 55 years and older (Table 2).

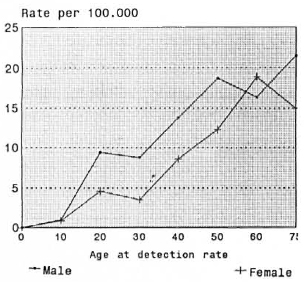

The Figure. Average detection rate per age at detection during period 1987-1990.

Annual detection rates. The average annual detection rates per year (1987-1990) increased from childhood (1 per 100,000) to the age group 55 and older (18 per 100,000). For the calculation of the rates the 1990 census was used. In the age groups 0-14 and older than 55 years of age, the detection rates in males and females were similar. In the age groups from 15 to 54 the detection rates for males were much higher than for the females (highly significant, p <0.001) (The Figure).

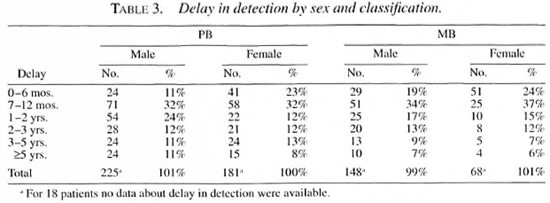

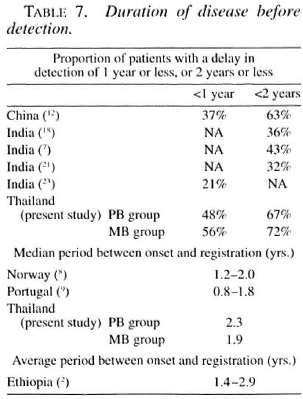

Duration of disease before registration: delay in detection. Data on the onset of disease showed that 56% of the MB and 48% of the PB patients had a delay in detection of 1 year or less, and 72% of the MB and 67% of the PB patients had a delay of 2 years or less (Table 3). Female PB patients report earlier than male PB patients, otherwise no statistically significant differences in proportions were found (between PB and MB patients, between female MB and male MB patients). The delay distribution is strongly positive skewed and a realistic mean, therefore, cannot be calculated. The median delay was 27.5 months (2.3 years) in the PB and 22.4 months (1.9 years) in the MB group.

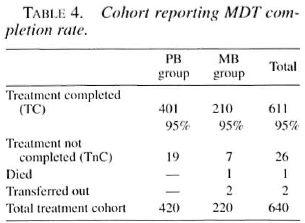

Cohort reporting WHO/MDT completion rate. The PB and MB WHO/MDT completion (TC) rates were both 95% (Table 4). Most patients finished their course of WHO/MDT in the shortest possible time. MB patients with a positive skin smear after 24 doses of WHO/MDT continued treatment until skin-smear negativity. Of the PB treatment not completed (TnC) group, 16 patients subsequently finished their course of WHO/MDT (and were released from treatment), only three patients being lost to follow up. Of the 7 patients of the MB TnC group, 5 patients subsequently finished their course of WHO/MDT and 2 patients were lost to follow up. In total, 632 patients (417 PB and 215 MB) were RFT.

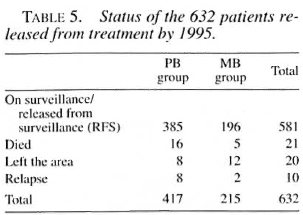

Status of 632 patients RFT by 1995. By the end of 1995, 385 of the 417 PB patients (92%) had been released from surveillance (and had not died, left the area or developed a relapse in the meantime) and 196 of the 215 MB patients (91%) were either still on surveillance or had been released from surveillance (Table 5).

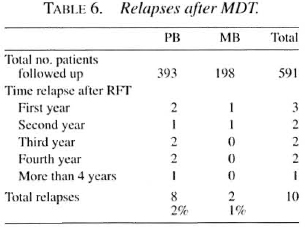

Relapses after MDT. By the end of 1995, eight PB and two MB relapses had been diagnosed (Table 6). Exact person-years of follow up cannot be calculated since the patients were only followed up passively after release from surveillance. It is estimated that 387 PB patients have been followed up for an average of 5 years and 201 MB patients for an average of 3 years. The relapse rates for PB and MB patients are 0.41 (0.21-0.82) and 0.33 (0.08-1.3) per 100 person-years at risk (PYAR).

Description of relapses PB group: 6 TT and 2 BT. In 2 TT patients, new lesions with positive skin smears (4 and 5 years after RFT, respectively); in 1 BT patient, new lesions with positive skin smears (1 month after RFT); in 1 TT and 1 BT patient, new lesions with negative skin smears (1.5 and 3.5 years after RFT, respectively); in 2 TT patients, an increase in size of old lesions (0.5 and 2 years after RFT), negative skin smear; in 1 TT patient, new activity (lesion more clearly visible and erythematous) in old lesion (2.5 years after RFT), negative skin smear (Table 6).

Description of relapses MB group: 1 BB and 1 BL. One BB patient (smear BI 3+) received MB MDT for 2 years: at RFT smear was negative; 1 year after RFT he presented with activity in the old lesions. Over the next 2 years the old lesions slowly increased in size, smears were repeatedly negative, and biopsies only mentioned resolving leprosy. One BL patient (smear BI 1+) received MB MDT for 2 years; at RFT smear was negative. Two years after RFT he returned with new lesions and activity in the old lesions (smear BI 1+ at several places). It was advised to take a biopsy and observe the patient for another 6 months, but the patient was restarted on MB MDT by the staff.

DISCUSSION

All newly diagnosed patients with no prior treatment were included in the study and followed up until the end of 1995. As seen from the cohort reporting (MDT completion rates) and the status of the RFT patients by 1995, only a few people were lost (dropped out, died, transferred) over the years. It is the experience of the leprosy control program of northeastern Thailand that patients report back to the provincial leprosy clinic in case of complications, even if they have temporarily migrated to other areas of the country for work (4). Even long-time migrants keep close contact with their home village (and vice versa).

Classification, age and sex distribution at diagnosis. The higher frequency of leprosy in male adults is a common finding, being especially marked among MB patients (5). In children the sex ratio is more equal. In this study there is one exception to the generally higher male/female ratio: in the PB group, in the age group 55 and older there is a higher female/male ratio. An easy explanation cannot be given. The higher numbers of females in this age group came mainly from voluntary reporting and not from active case finding as may have been expected. Some overdiagnosis cannot be excluded, although most new patients were re-examined by the regional leprosy control team within 1 month of registration. If immunological changes in the elderly could be a factor, why should this affect women more than men? Figure I hints at the fact that women fall sick at a later age than men (9), but we have to keep in mind that these are case-detection and not incidence rates (and age at detection rather than age at onset). A higher frequency of leprosy in female adults has been reported from some parts of Africa (5), but this is not the case in this study. The suggestion that the lower frequency of leprosy in women may reflect ascertainment bias rather than true sexual differences would be an unlikely explanation for the lower frequency of leprosy among women in northeastern Thailand (10, 24). For example: if there would have been an ascertainment bias, more women with severe impairments would have been found, especially in the older age groups. Such is not the case (see part III of this study).

Case-detection rates. New case-detection rates have been declining in the three provinces and in Thailand as a whole, with an average annual decline of 10.0% for the period 1979-1990 (17, 19), In the study area the detection rates were 19 per 100,000 in 1984, 7 per 100,000 in 1989 (average 1987-1990), and 5 per 100,000 in 1994. The detection rates per age group show a much higher rate in the elderly, declining toward the younger age groups (Fig. 1). From the data of this study alone, age-specific incidence rates by year of onset or by year of birth cannot be calculated. Nevertheless, these detection rates seem to suggest a sharp decline in leprosy incidence rates in successive birth cohorts over the last 50 years (8-10). Although, doubts can be raised about the approximation of incidence rates by detection rates, the specialized program of these three provinces in northeastern Thailand has a long record of good (and stable) case-finding activities. In Thailand, the mean age at detection increased by nearly 7 years over the period 1976-1990 while new case detection decreased. This age shift in detection seems to suggest a real age shift in incidence (17).

Duration of disease before registration. Interviewing patients about the history of their disease (recall) and especially when (and how) it started is generally considered not to be very accurate. However, the interviewing was consistent throughout the study period. Table 3 suggests that women report earlier (only in the PB group was it statistically significant) and that MB patients report earlier than PB patients (not statistically significant). The relationship between impairment prevalence and duration of disease (between onset disease and detection/diagnosis) was found to be statistically significant (part III of this study), suggesting some validity of the data.

In several studies from India, the majority of newly detected leprosy patients had a delay of more than 2 years (Table 7). In a study from China, 37% of new patients were detected within 1 year after onset and 63% within 2 years (12). From Ethiopia an average delay was 1.4-2.9 years (shorter in PB, longer in MB patients) (2). The median delay periods reported from Norway (8) and Portugal (9) are shorter than those found in this study from Thailand (Table 7). Preliminary results of WHO collaborative studies indicate that the majority of new cases are detected late, even in programs that have used MDT for many years (17).

In our study area a leprosy control program has been active for more than 30 years. Over those years in Thailand there has been rapid socioeconomic development with at present a good health infrastructure which is easily accessible. Data from the same area show that there has been a gradual improvement, with more patients reporting earlier, over the years. Nevertheless, 6% of the PB and 10% of the MB patients already had visible impairments when they reported for treatment (part III of this study).

Treatment completion. For the outcome indicator for chemotherapy completion (WHO/MDT) the treatment completion (TC) rate was used. These TC rates were very high, which is understandable since most patients received their monthly treatment at home. Intake compliance (daily intake of dapsone and clofazimine) was not checked.

Occurrence of relapse. Most patients who develop new clinical activity during the first few years after RFT appear to be suffering from a late reaction (1). Late reactions occur mostly within 3-4 years after RFT (3). The longer the period after RFT, the higher the chance that signs of new clinical activity signify a relapse (4). However, very late reactions may occur, and the longest treatment-reaction interval reported has been 6.5 years (15).

Guidelines have been provided to differentiate between a late reaction and a relapse (1), but this remains a difficult area. In this study the diagnosis of a relapse was not always evident and, in some cases, reasonable doubt was raised about the accuracy of the diagnosis. In both MB patients the diagnosis of a relapse can be questioned. In the case of the BL patient a second set of skin smears should have been taken after 6 months; the BB patient (originally smear BI 3+) came back 1 year after RFT with a gradual but marked increase in the size of old lesions which continued (increasing in size) over the next 2 years (smears and biopsies being repeatedly negative). This is a doubtful relapse, and could have been a mild late reversal reaction or even a PB relapse in a MB patient. One PB patient (new activity, old lesion) was recorded as a relapse but did not, in fact, meet the criteria accepted by the project. In two other patients (increase in size of old lesions) the diagnosis of a relapse can be considered doubtful. Biopsies are often not helpful in the diagnosis of a relapse (4). The three PB patients who relapsed with a positive skin smear had probably been misclassified in the first place (especially the PB patient who relapsed within 1 month after RFT).

Even if we doubt the diagnosis of a relapse in several patients, these relapse rates compare very well with other studies on relapse in leprosy (26, 30). The average period of follow up was rather short, especially in the MB group. However, since our MB skin-smear-positive patients were treated until skin-smear negative, a high relapse rate among the original highly positive BL and LL patients is not expected (26).

Study under routine program conditions. This study was implemented under routine program conditions, albeit a vertically organized one, with regular input from a specialized team from the Regional Leprosy Control Center, Khon Kaen. One should be aware that "the diagnosis of leprosy often is a difficult matter, that its classification is controversial, and that we are faced with problems of comparability between case series from different regions and workers" (6). This may be even more so when it comes to the diagnosis of reaction and neuritis (14), the assessment of nerve function in leprosy patients (13 and the diagnosis of a late reaction and relapse. Especially during the first year of study, the combination of case detection and case holding with the early detection of NFI and the prevention of impairments and disabilities proved for many leprosy lieldworkers to be a difficult task (16). Regularity of POD examination and recording by lieldworkers was a problem throughout the study, although quality of referrals (patients referred earlier) improved remarkably during the study.

Acknowledgment. I am gratelul to the Netherlands Leprosy Relief Association (NSL) and the Leprosy Division, Department of Communieable Disease Control, Ministry of Health, Thailand, for the opportunity to carry out this study. I thank especially the staff of the Provincial Leprosy Control Offices Mahasarakham, Roi-et and Kalasin and of the Regional Leprosy Control Center, Khon Kaen, northeastern Thailand (Ms. Prakong Thiabsri and Mr. Piya Piyasilpa), and the VSO and NSL physiotherapists. Sincere thanks are also due to those who contributed to the analysis of the data and to those who reviewed drafts of the report.

REFERENCES

1. BECX-BLEUMINK, M. Relapses among leprosy patients treated with multidrug therapy: experience in the Leprosy Control Program of the All Africa Leprosy and Rehabilitation Training Center (ALERT) in Ethiopia: practical difficulties with diagnosing relapses; operational procedures and criteria for diagnosing relapses. Int. J. Lepr. 60(1992)421-435.

2. BECX-BLEUMINK, M. Priorities for the future and prospects for leprosy control. Int. J. Lepr. 61(1993)82-101.

3. BECX-BLEUMINK, M. and BERHE, D. Occurrence of reactions, their diagnosis and management in leprosy patients treated with multidrug therapy: experience in the Leprosy Control Program of the All Africa Leprosy and Rehabilitation Training Center (ALERT) in Ethiopia. Int. J. Lepr. 60(1992)173-184.

4. DASANAJALI, K., SCHREUDER, P. A. M. and PIRAYAVARAPORN, C. A study of the effectiveness and safety of the WHO MDT regimen in the northeast of Thailand, a prospective study, 1984-1996. Int. J. Lepr. 65(1997)28-36.

5. FINE, P. E. M. Leprosy: the epidemiology of a slow bacterium. Epidemiol. Rev. 4(1994)161-187.

6. FINE, P. E. M. Problems in the collection and analysis of data in leprosy studies. Lepr. Rev. 52 Suppl. 1(1981)197-206.

7. GlRDHAR, M., ARORA, S. K., HOHAN, L. and MUKHIJA, R. D. Pattern of leprosy disabilities in Gorakhpur (Uttar Pradesh). Indian J. Lepr. 61(1989)503-513.

8. IRGENS, L. M. Leprosy in Norway, an epidemiological study based on a national patient registry. Lepr. Rev. 51 Suppl. 1(1980)1-130.

9. IRGENS, L. M., MELO CAEIRO, F. and LECHAT, M. F. Leprosy in Portugal 1946-80: epidemiologic patterns observed during declining incidence rates. Lepr. Rev. 61(1990)32-49.

10. IRGENS, L. M. and SKJAERVEN, R. Secular trends in age at onset, sex ratio, and type index in leprosy observed during declining incidence rates. Am. J. Epidemiol. 122(1985)695-705.

11. KlRKWOOD, B. R. Essentials of Medical Statistics. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific, 1988.

12. LI, H. Y., WENG, X. M., LI, T. ZHENG, D. Y., MAO, Z. M., RAN. S. P. and LIU, F. W. Long-term effect Of leprosy control in two prefectures of China, 1955-1993. Int. J. Lepr. 63(1995)213-221.

13. LIENHARDT, C., CURRIE, H. and WHEELER, J. Inter-observer variability in the assessment of nerve function in leprosy patients in Ethiopia. Int. J. Lepr. 63(1995)62-76.

14. LlENHARDT, C. and FINE, P. E. M. Type I reaction, neuritis and disability in leprosy. What is the current epidemiological situation? Lepr. Rev. 65(1994)190-203.

15. LOCKWOOD, D. N. J., VINAYAKUMAR, S., STANLEY, J. N. A., MCADAM, P. W. J. and COLSTON, M. J. Clinical features and outcome of reversal (type 1) reactions in Hyderabad, India. Int. J. Lepr. 61(1993)8-15.

16. MCDOUGALL, A. Leprosy control and the implementation of multiple drug therapy: to what extent can the operational strategy be simplified for primary health care? Lepr. Rev. 63(1992)193-198.

17. MEINEMA, A., GUPTE, M. D., VAN OORTMARSSEN, G. J. and HABBEMA. J. D. F. Trends in leprosy ease detection rates. Int. J. Lepr. 65(1997)305-319.

18. NOORDEEN, S. K. and SRINIVASAN, H. Epidemiology of disability in leprosy. 1. A general study of disability among male leprosy patients above fifteen years of age. Int. J. Lepr. 34(1966)159-169.

19. PIRAYAVARAPORN, C. and PEERAPAKORN, S. The measurement of the epidemiological impact of multidrug therapy. Lepr. Rev. 63 Suppl. (1992)84s-92s.

20. PÖNNIGHAUS, J. M. and BOERRIGTER, G. Are 18 doses of WHO/MDT sufficient for multibacillary leprosy; results of a trial in Malawi. Int. J. Lepr. 63(1995)1-7.

21. SAHA, S. P. and DAS, K. K. Disability pattern amongst leprosy eases in an urban area (Calcutta). Indian J. Lepr. 65(1993)305-314.

22. SMITH, W. C. S. The epidemiology of disability in leprosy including risk factors. Lepr. Rev. 63 Suppl. (1992)23s-30s.

23. THAPPA, D. M., KAUR, S. and SHARMA, V. K. Disability index of hands and feet in patients attending an urban leprosy clinic. Indian J. Lepr. 62(1990)328-337.

24. ULRKTI, M., ZULUETA, A. M., CACERES-DITTMAR, G., SAMPSON, C, PINARDI, M. E., RADA, M. E. and ARANZAZU, N. Leprosy in women: characteristics and repercussions. Soc. Sci. Med. 37(1993)445-456.

25. VAN BRAKEL, W. H., KHAWAS, I. B. and LUCAS, S. Reactions in leprosy: an epidemiological study of 386 patients in west Nepal. Lepr. Rev. 65(1994)190-203.

26. WATERS, M. F. R. Relapses following various types of multidrug therapy in multibacillary leprosy. Lepr. Rev. 66(1995)1-9.

27. WATSON, J. M. Essential Action to Minimise Disability in Leprosy Patients. London: The Leprosy Mission, 1986.

28. WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION, A Guide to Leprosy Control. 2nd edn. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1988.

29. WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION. Chemotherapy of leprosy for control programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1982. Tech. Rep. Ser. 675.

30. WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION. The Leprosy Unit, Division of Control of Tropical Diseases. Risk of relapse in leprosy. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1994. WHO/CTD/LEP/94.1.

P. A. M. Schreuder, M.D., M.Sc, Leprosy Control Center Region 6. Khon Kaen, Thailand.

Reprint requests to Dr. Schreuder at his present address: NSL Medical Officer, Fast Java Leprosy Control Project, Provincial Health Office, JI. Karangmenjangan No. 22, Surabaya 60285, Indonesia.

Received for publication on 3 February 1998.

Accepted for publication in revised form on 17 April 1998.