- Volume 61 , Number 4

- Page: 619–27

A singular obsession: new brunswick's leprosy doctor

Editorial opinions expressed arc those of the writers.

In leprosy's long history, the second half of the 19th century was a significant turning point marked by the emergence of a distinct group of specialists called leprologists. Carving out a distinctive professional niche for themselves, they launched their first International Leprosy Congress in 1897 and began publishing their own multilingual journal, Lepra, 2 years later. This surge of interest in leprosy was closely linked to two factors. First, G.H. Armauer Hansen's identification of the rod-shaped leprosy bacillus in 1873 propelled the disease to the forefront of bacteriological inquiry and public concern. Secondly, as the alleged contagiousness of leprosy gained notoriety a widespread leprophobia hardened into government policies mandating specifically designed leprosy colonies and the compulsory segregation of persons with the disease.

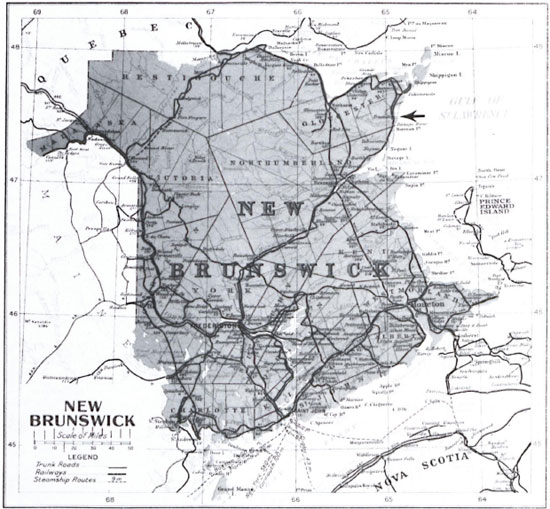

Numbered among the exclusive cadre of leprologists was Dr. Alfred C. Smith, medical superintendent of the Tracadie lazaretto, located in a remote village in northeastern New Brunswick, Canada (Fig. 1). The price of Smith's physical isolation from the major medical centers of the 19th century was ultimately undeserved neglect. However, the private papers of this little known physician reveal that he counted among his colleagues the leading dermatologists and leprologists of his time, including Drs. Jonathan Hutchinson, James White, Isadore Dyer, Albert Ashmead, and George Pernet, editor of Lepra. Some of these medical luminaries even paid Smith the compliment of making a pilgrimage to Tracadie, such as Dr. James E. Graham, one-time Vice-President of the American Dermatological Association; George Fox, a leading American dermatologist; the legendary Dr. William Osier, and Dr. Henry Stelwagon, the renowned American author of A Treatise on Diseases of the Skin. Their visits were only partially motivated by professional curiosity. They also wanted to make the acquaintance of the remarkable doctor who had transformed the Tracadie lazaretto into a model institution.

Fig. 1. Map of the Province of New Brunswick, Canada, c. 1915. This map shows the coastal village of Tracadie (←) in Gloucester County facing the Gulf of St. Lawrence (Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, 203 c. 1915).

Little is known about the formative years of this original and unconventional physician. Alfred Smith was born in 1841 in Tetagouche, near Bathurst, New Brunswick, the son of James Smith, one-time grammar school teacher, school inspector and merchant, and Susanna M. Dunn. By 1858, however, Alfred Smith fastened his sights on a medical career. At the time it was customary for a student to spend 1 or 2 years under the tutelage of a preceptor before undertaking formal medical school education. Dr. James Nicholson, the first resident physician at the Tracadie lazaretto, acted as Smith's preceptor. No more than 7 years separated pupil and tutor. Nevertheless, Nicholson obviously had a profound influence on the young Smith, especially in determining his choice of leprosy as a specialty. In the fall of 1862, Smith headed for Massachusetts Medical College (later Harvard Medical School) in Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.A, which at the time was swept up in abolitionist fervor. Here he received his medical degree in March 1864.1

Regrettably, no letters survive detailing his training in Boston, but it is clear that he was exposed to the teachings of Drs. Henry Bowditch, Henry J. Bigclow and Oliver Wendell Holmes. It was, however, Dr. James White, then only a part-time lecturer on skin diseases at the college, who had a lasting impact on Smith.

Oddly enough, Smith never pursued postgraduate studies in Paris, Berlin or even Vienna, despite the fact that these were the well-traveled routes to medical prestige. Instead, he returned to New Brunswick in 1865 to become resident physician at the Tracadie lazaretto when the post was left vacant by Nicholson's death. The institution was little more than a rustic and rambling oneand-a-half-storey frame structure. With a steep-pitched roof and scattered outbuildings, it had an almost medieval appearance. Three years later, Smith was dismissed, the casualty of a money-saving measure. By the 1870s he had relocated as a family physician in Newcastle, New Brunswick. But he refused to settle into a comfortable routine, and interrupted his private practice in 1877 to undertake postgraduate work at New York University School of Medicine. Here he attended winter and spring lecture sessions and expanded his clinical skill at the Bellevue Hospital and Charity Hospital on Blackwell's Island, where many of the patients were treated for contagious disorders.2 Subsequently, in 1884, he moved temporarily to Toronto, Ontario, Canada, where he enrolled in a full complement of courses, including midwifery, physiology, chemistry and botany, at the Medical Faculty of Victoria University.3

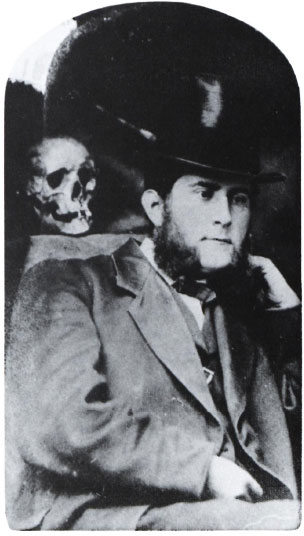

Judging from old photographs, Dr. Smith was a striking personality (Fig. 2). His slightly gaunt face, encircled by woolly mutton chops, and his piercing dark eyes projected a commanding presence. The initial impression he left was an almost antisocial aloofness. He seemed to revel in defying conventions and conformity. In fact, at times the Tracadie leprosy doctor could be crusty and opinionated, and his papers are peppered with such marginalia as "trash," "humbug," and "Thank God, I don't know German." And yet he had redeeming qualities, most notably his generosity and compassion. He refrained from intimidating his leprosy patients with scientific terminology and treated them with a paternal solicitude.

Fig. 2. Dr. Alfred C. Smith (1841-1909) as a young physician (Centre de Documentation de la Société Historique Nicolas-Denys, A17 #15).

Nevertheless, to the townspeople of Tracadie, this bookish, solitary figure was an enigma. His eccentricities disconcerted them, especially his eclectic religious views- a product of his first-hand brush with Unitarianism at Harvard-which people misconstrued as atheism. Smith also emitted a fearful "all knowingness" which gave rise to the rumor that he tapped the telegraph lines and eavesdropped "so he could amaze people with his knowledge of their private affairs."4 He was also a secretive person. Privacy, in fact, became a personal fixation; while living in Newcastle, he even constructed a high fence to shield his movements between his home and adjacent medical office. Although seeming remote and scholarly, Smith did have his moments of whimsy. When the Harvard Medical School wrote enquiring in 1904 as to his whereabouts, he puckishly stroked out the words "Death [Place]," and wrote, "Feels very much alive today."5 His sense of humor, typical of medical students of every age, tended to be macabre. According to local folklore, he was not above placing a skull on a neighbor's doorstep. His stove, it is alleged, stood on a tombstone and the upper room of his office was modeled on the interior of a hearse. Notwithstanding such idiosyncrasies, Smith was very much the embodiment of the scientifically inclined, inquisitive Victorian. He harnessed this enthusiasm in several hobbies. He was an avid photographer and a keen devotee of natural history. He even dabbled in taxidermy and archeology.

Despite these leisure-time activities, leprosy was the all-consuming focus of Smith's career. He made no secret of his "long felt desire to throw myself wholly into the study of leprosy" and to make the disease "the special study" of his life.6 Smith's private papers vividly reveal the completeness and totality of his dedication to the care and treatment of his leprosy patients. He eagerly collected books, articles, manuals and newspaper clippings on the disease, amassing what he claimed to be the most complete library in Canada of medical literature on leprosy. To specialize in leprosy had a magnetic appeal to Smith. On occasion, he fantasized about inoculating himself with the bacillus of one of his patients, passionately confessing "I have long thought over the matter, and the more I think about it the better I like the idea."7 The specialty, which eventually drove away his regular clients, robbing him of his private practice and confining him to the laboratory and the leprosy wards, apparently satisfied the deeper recesses of his character. In fact, this singular obsession, which was very much on the fringe of medical science, shaped the whole texture of his life and career.

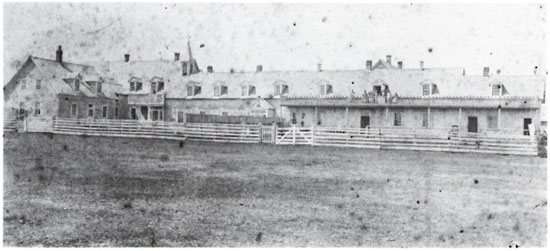

It was Smith's interest in leprosy which fueled his ambition to become full-time physician at the Tracadie lazaretto (Fig. 3). In 1880, he was appointed "Inspecting Physician" and "Medical Advisor" to that institution but, as late as 1889, a more permanent position still eluded him. That year, Smith vigorously lobbied the Canadian government to enlarge his professional duties so that he could give his "whole time and study to the general superintendence of this disease in Canada."8 Pointedly, he reminded officials that leprosy had already secured a foothold in northern New Brunswick and was making inroads in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. The endorsement of Dr. William Osier gave a timely fillip to Smith's cause. Osier urged the government to appoint a full-time lazaretto superintendent, arguing that "Dr. Smith has been in touch with physicians on the subject all over the world, and has the necessary skill... I know of no one more suitable for the position should you create it."9

Fig. 3. The second Tracadie lazaretto, c. 1887 (the first was built in 1849 and burned in 1852) with its many makeshift extensions shortly before the completed construction of the new one in 1896. The unpainted and rambling frame structure was described in the mid- 1880s as "old, cold, and a pile of decaying wood" (Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, P20-277).

In November 1889, the Canadian government conferred on Smith the grandiose sounding title of "Inspector of Leprosy for the Dominion," but the victory was a hollow one. His remuneration was a pittance; the annual salary of $600 and a travel allowance of $200 were hardly "sufficient for family expenses."10 Smith also found his professional aspirations repeatedly thwarted by the popular consensus that leprosy was absolutely incurable and inevitably fatal. Such conceptions dictated that the lazaretto should be a "home" rather than a "hospital." In other words, the physician's role was irrelevant, for the leprosy patients required only custodial care. Smith had to wait another 10 years before the Canadian government finally resolved to administer the Tracadie leprosy hospital on a more scientific basis and elevated him to the rank of "Medical Superintendent." It was a significant development, denoting official recognition of the leprologist's qualifications as a medical specialist.

With this promotion, Dr. Smith obtained the security and affirmation he had always craved. His daily workplace was the newly constructed Tracadie lazaretto (Fig. 4), a massive three-storey stone structure with an imposing cruciform shape, mansard roof and verandas. A far cry from its rustic predecessor, the new structure, completed in 1896, contained roomy living quarters for the patients and a sizable staff of nursing sisters belonging to the Order of the Religious Hospitallers of St. Joseph (Fig. 5)." For the first time, Smith enjoyed having a permanent office on the hospital premises. Henceforth, his personal and professional existence became virtually coterminous with the lazaretto in Tracadie. Even his residence, where he lived with his wife and three children, was not beyond the reach of the long shadow of the lazaretto. Its physical proximity was further reinforced in 1906 when Smith installed two telephones in his house, including one in his bedroom, so that he might have "daily and nightly connection" with the lazaretto.12

Fig. 4. The Tracadie Lazaretto, c. 1900. The left wing housed the Sisters' convent and the right wing with its partial verandahs served as wards for the leprosy patients (the males on the first storey, the females segregated on the second). Behind the white picket fence to the right was the patients' garden where they could grow flowers and vegetables. Dr. Smith's office was to the left of the main entrance and the pharmacy to the right. Extending to the rear was a hospital wing (Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, P6-43).

Fig. 5. The Religious Hospitallers of Saint Joseph Sisters and their patients at the Tracadie Lazaretto, c. 1875 (Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, P67-3).

Smith's duties at the leprosy hospital were as varied as they were arduous. He visited the wards daily, frequently performed surgical and dental procedures, and spent a portion of each day engaged in laboratory research. He was also entrusted with such matters as diet, hygiene and discipline. Within his jurisdiction fell the preparation of annual government reports, maintenance of registers of admissions, ward visits and prescriptions, compilation of genealogical data on leprosy families, correspondence with the families of patients and the fumigation of railway cars used to transport leprosy sufferers. Smith's duties often took him outside the lazaretto wards on "tours of inspection," which he facetiously dubbed leprosy "hunting."13 Armed with a "Hawkeye" camera and notebook, he periodically crisscrossed northern New Brunswick, visiting various households and local lobster canneries and fish-packing plants. On these trips, he would track down and diagnose leprosy "suspects" and would employ the requisite mixture of compassion and coercion to secure their admission to the lazaretto. The formula he devised was swiftly efficient: "When I declare an individual leprous, his nearest friends avoid him; he is refused employment, and he soon finds a resting place in the home provided for such unfortunates."14 For those people falsely tarred as having leprosy by public opinion, he issued the much prized "Certificates of Freedom From Leprosy." Visitations and diagnostic examinations were sometimes fraught with hazards. Smith reported that he had "guns fired near me in a menacing manner ... been threatened with physical violence, and ... sat listening by the hour to abusive language."15 In 1889, he traveled further afield to Cape Breton to investigate rumored "outbreaks of leprosy."16 In the spring of 1891, he was despatched to Victoria, British Columbia, where he diagnosed leprosy in five patients and authorized their removal to D'Arcy Island, Canada's Pacific Coast lazaretto. In 1897 and 1907, he journeyed to Winnipeg, to examine suspected cases of leprosy among Icelandic immigrants.

The widely read Smith maintained distinctive views about the etiology and treatment of leprosy. Throughout the 1880s, he was neither a dogmatic contagionist nor a rigid hereditarian. He mulled over the diverse arguments for innate susceptibility, environmental causation and inoculation, willing to test the soundness of all options. It was not until 1904 that his opinions finally crystallized. By then, he was unequivocally convinced of leprosy's contagious character.

One of Smith's most striking trademarks was his diagnostic caution. For him, diagnosis was an act of gravity, while misdiagnosis was "a terrible and inexcusable error."17 Smith knew only too well that lupus, psoriasis and syphilis could often pass deceptively for leprosy. The medical regimen which Smith prescribed for his patients was also marked by prudence. Although conversant with the popular antileprotics of the day, such as gurjun oil, Carrasquilla's serum and Leprolin, Smith did not condone excessive experimentation or leap at each passing fad. In his supportive and curative therapies, he preferred to err on the side of moderation, often extolling the palliative benefits of sound hygiene and nutritious diet. These principles, he claimed, not only ameliorated the leprosy sufferers' moral and physical well-being, but also extended their life expectancy. Smith did not close his mind completely to more radical treatments. After monitoring its progress for 4 years, he finally decided to test the efficacy of ichthyol on some of his own patients. He also experimented briefly with a decoction made from the leaves, twigs and seeds of the tuatua plant, as well as a eucalyptus compound; both were employed at the leprosy colony in Hawaii. Chaulmoogra oil, however, was the keystone of Smith's medical regimen at the Tracadie lazaretto. In 1884, he introduced the oil to some of his patients but with negative results. In 1902, he resumed its use both orally and externally, sometimes in combination with creolin and strychnine. To lessen its unpleasant taste and odor, Smith frequently diluted the dosages with syrup of wild cherry bark. Although few patients, even the less-advanced cases, could tolerate its extended use, Smith waxed enthusiastically about chaulmoogra oil's healing properties. Unlike many of his leprologist contemporaries, he was optimistic about the potential curability of leprosy. In fact, he did not consider the idea of a "specific" visionary. Although his therapeutic optimism faded by the turn of the century, Smith's belief in the effectiveness of chaulmoogra oil was unwavering. He gave the natural cure his unequivocal endorsement, claiming in 1907: "I believe that chaulmoogra oil, in combination, will cure leprosy if begun before serious inroads have been made on the constitution, and if maintained long enough."18 Unlike many of his colleagues, Smith also believed in "spontaneous recovery." In at least five instances, the Tracadie doctor had witnessed full recoveries or extended remissions. These medical conundrums served to remind him of leprosy's inconsistencies and the folly of dogmatism.

Only on one point did Smith prove himself inflexible. He regarded compulsory segregation an essential component in the treatment and containment of leprosy. Dismissing a relaxed approach to the disease as impractical idealism, he battled for more stringent legislation for the apprehension, detention and medical supervision of leprosy patients. From his perspective, leprosy was both a medical and a management problem requiring compulsion tempered by compassion.

Owing to the fact that Smith committed so few of his ideas about leprosy to paper, it is difficult to determine what medical authors or leprologists moulded his opinions. Nevertheless, although compelled to pursue his career in the backwaters of northern New Brunswick, he clearly did not stagnate professionally or intellectually. Throughout his career, he demonstrated an eagerness to expand and update his knowledge. He was particularly intent on honing his research techniques. The fact that he never received any formal laboratory training proved a handicap in his technical development. Occasionally, he mused about going to Harvard Medical School or the University of Michigan for a more intensive introduction to bacteriology. The main stumbling block to these plans was an unsupportive Canadian government. Smith's request for leave to study at McGill University, for example, was greeted with an official remonstrance about his overriding professional commitments to the lazaretto. When he was invited to attend the 1897 Leprosy Congress as a delegate, the government declined to subsidize his trip to Berlin. Aggrieved by the government's short-sighted stinginess, Smith retorted "Leprologists the world over expect me to add my quota to the sum total of knowledge on the subject ... and I find myself seriously handicapped for want of scientific instruments."19

Thwarted in his own forays into laboratory research, Smith was not shy about soliciting the expertise of others. In 1897, John T. Bowen, an expert histopathologist and assistant physician in the outpatient department for skin diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital, coached Smith by letter, advising him about procedures for staining and mounting slides, removing tubercles and employing a cutaneous punch. By that date, Smith considered the microscope an indispensable diagnostic tool; in fact, he regarded bacteriological confirmation a requisite precondition to institutional commitment. In this work, he was assisted by both Drs. Bowen and James White, to whom he mailed off small packages of tissue and smears for analysis. Smith also corresponded on a consultative basis with Prince Morrow, whom he visited in New York in the fall of 1890, learning first hand of the latter's recent research expedition to Hawaii.

Such contacts must have done much to mitigate Smith's lonely existence and satisfy his appetite for collegial interaction. Occasionally, however, his correspondence brought unwelcome notoriety and embarrassment. In January 1904, for example, Smith found himself quoted in the London Times by the celebrated Jonathan-Hutchinson. The Tracadie physician was redfaced that one of his letters had been marshalled as evidence to support Hutchinson's fatuous theories about leprosy and fish-eating. Smith's letters with the Louisiana leprologist Dr. Isadore Dyer also prompted conflict. Together the two men explored the possibility of a relationship between leprosy in Louisiana and that in the Maritime Provinces of Canada, although Smith balked at Dyer's attempts to tie the genesis of leprosy in Louisiana to the deportation of the Acadians in the 1750s. Much more compromising were Smith's exchanges with Dr. Albert Ashmead. In all innocence, Dr. Smith helped fuel Ashmead's odious theories about leprosy and racial regression, having once commented that the leprosy patients "in New Brunswick are degenerated French."20 Again, he found his name associated with a crude theory with which he really had little sympathy.

It should be noted that in 1901 the Canadian government finally outfitted Smith with a fully equipped laboratory. But this concession came too late. By then, glaucoma seriously interfered with his research. In retrospect, it is difficult to gauge the significance of Smith's research. It is regrettable that he published nothing about his laboratory work. In his private papers, however, he mentioned the use of microphotography and detailed complex staining procedures. An American bacteriologist once praised him: "It would be hard to beat your specimens."21

Smith, however, never became as eminent as the specialists with whom he corresponded. There is no easy explanation for his unrealized potential. Undoubtedly, Smith's zeal was drained by a callous government, the stubborn incurability of his patients, and the unrelieved tedium of his job. Ill health also took its physical and professional toll. Glaucoma frustrated his research, and during the winter of 1907-1908, he was virtually paralyzed by rheumatism which flared up after he had completed the chilling nine-hour task of fumigating an unheated railway car. The following year was marred by insomnia, mental exhaustion and a series of strokes. Smith died on 12 March 1909. Interestingly enough, his passing attracted the attention of the New York Times, which ran the sensational headline, "Expert on Leprosy Dies. Physician to New Brunswick's Leper Colony Recently announced a cure."22 Even though his death went unacknowledged in the Canada Lancet and The Canadian Practitioner, notices did appear in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal and the Journal of the American Medical Association.23 These were, however, little more than cursory references. It was from his "inconsolable" leprosy patients that Smith's death elicited the most poignant response. It is recorded that they bolted from the hospital wards, scattered across the nearby field, and headed for Dr. Smith's residence (Fig. 6), where they were greeted by his widow. Sensing their grief, she "accorded them the privilege of entering the room where his remains were laid out."24

Fig. 6. Dr. Smith's house and office in Tracadie sometime after his death (Private Collection).

Clearly, Smith's most tangible memorial was the Tracadic leprosy hospital. Under his medical superintendence, the lazaretto was both modernized and humanized. Unwavering in his vision that the lazaretto should be more than a detention center or a religious hospice, Smith ensured that it functioned as both a "hospital" and a "home." The Tracadie lazaretto also epitomized the application of moderation and practical scientific principles. As such, it became the highly acclaimed exemplar for leprosy institutions around the world. This international reputation was due in no small part to the lazaretto's caring and capable Medical Superintendent. For this reason alone, Dr. A. C. Smith deserves to be remembered more widely than he is.25

- Laurie C. C. Stanley-Blackwell, Ph. D.

Assistant professor

Department of History

St. Francis Xavier University

Antigonish, Nova Scotia

Canada B2G ICO

1. Archives, Boston Medical Library -Harvard Medical Library, AA 17.5, vol. 1 "Graduates with their Theses 1856-1864."

2. Van B. Afes (Archivist of the New York University Medical Center) to author, 9 July 1984. Sec also The Annual Announcement for the Session 1877-78 (University of the City of New York Medical Department).

3. Archives, Victoria University, "Schedule of Candidates for Examination at Medical Board," 1884.

4. W. Brenton, Medicine in New Brunswick (Moncton: 1974) 238.

5. Mary Van Winkle to L. Stanley-Blackwell, 22 May 1986. This information was extracted from the Biographical File on Harvard Medical School Graduates, compiled c. 1905.

6. Le Centre de Documentation de la Société Historique de Nicolas-Denys, Shippagan, N. B. [henceforth CD-SHND] Box 105-1, File 1; Smith to "Dear Sir" 24 Sept 1890; also Smith to Minister of Agriculture, 23 May 1889.

7. CD-SHND, album 105-7, 56; undated clipping "May become a Leper."

8. National Archives of Canada [henceforth NAC] RG 17, A. 1.1, vol. 623; Smith to Lowe, 17 Sept 1889.

9. Ibid., vol. 624; Osier to Minister of Agriculture, 22 Sept 1889.

10. Ibid., vol. 685; Smith to Lowe, 8 May 1891.

11. The new stone lazaretto was designed to accommodate about 50 patients, but it never housed more than about half that number at any one time. From 1844 to 1965, approximately 325 people diagnosed with leprosy were institutionalized in New Brunswick, first on Sheldrake Island (1844-1849) and then at Tracadie. The last two cases from New Brunswick entered the Tracadie lazaretto in 1937. During the last 28 years of its existence, this institution received only a trickle of patients, coming from such varied origins as China, Malta, Russia and Lithuania. Shortly before the lazaretto's closure in 1965, the last patient was relocated in a nursing home where she died in 1969.

12. NAC, RG 29, vol. 5, File 937015 ½ pt. 5; Smith to Montizambert, 11 October 1906.

13. Historical Collections, Library' of the College of Physicians, Philadelphia; Smith to Ashmead, 18 Aug 1897.

14. Canada Sessional Papers, vol. 6, 1900, appendix 11; Report on the Lazaretto, Tracadie, 31 Oct 1899, p. 91.

15. NAC, RG 29, vol. 300; Smith to Montizambert, 8 Jan 1906.

16. CD-SHND, Box 105-1, File 1; Smith to Minister of Agriculture, 23 May 1889.

17. Canada Sessional Papers, vol. 6, 1900, appendix 1 1; Report on the Lazaretto, Tracadie, 31 Oct 1899, 91.

18. Ibid., vol. 7, 1908, appendix 12; Smith to Minister of Agriculture, 31 March 1907, 16.

19. NAC, RG 29, vol. 5, File 937015 ½ pt. 2; Smith to Scarth, 25 May 1897.

20. Albert Ashmead, "Introduction of Leprosy into Nova Scotia and the Province of New Brunswick, Micmacs Immune," The Journal of the American Medical Association, XXVI, 1 Feb 1896, 203, 207.

21. CD-SHND, Box 105-5, File 11; Cowic to Smith, n.d. [c. 1901].

22. New York Times, 21 March 1909.

23. Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. LII (3 April 1909) no. 14, p. 1131; Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, vol. CLX (18 March 1909) p. 356. A more detailed account of Dr. Smith's remarkable career can be found in Laurie C. C. Stanley, "Leprosy in New Brunswick 1844-1910: A Reconsideration" (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. Queen's University, 1989).

24. Archives of the Religious Hospitallers of St. Joseph, Tracadic, Annales 1909, 185.

25. Today visitors to Tracadic can see artifacts related to the history of this institution at the Musée Historique de Tracadic and visit the hospital cemetery.